Essays

Mapping Freedom

Let me begin with a quote from, of all people, Bob Dylan, remembering 1960 or so, when he was about 20:

"I couldn't exactly put in words what I was looking for, but I began searching in principle for it, over at the New York Public Library. In one of the upstairs reading rooms I started reading articles in newspapers on microfilm from 1855 to about 1865 to see what daily life was like. I wasn't so much interested in the issues as intrigued by the language and rhetoric of the times.As Dylan says, the Civil War was "all one long funeral song." But out of that funeral song came the most remarkable act of emancipation in modern history: four million people become free, with no compensation to the slaveholders and with a determination to bring justice as well as freedom to those held in bondage for more than two centuries.

. . . Everybody uses the same God, quotes the same Bible and law and literature. . . . You wonder how people so united by geography and religious ideals could become such bitter enemies. After a while you become aware of nothing but a culture of feeling, of black days, of schism, evil for evil, the common destiny of the human being getting thrown off course. It's all one long funeral song, but there's a certain imperfection in the themes, an ideology of high abstraction, a lot of epic, bearded characters, exalted men who are not necessarily good. . . . The suffering is endless, and the punishment is going to be forever. It's all so unrealistic, grandiose and sanctimonious at the same time."1

It's that pivot that currently concerns me, that apparent contradiction between a war that people stumbled into and a glorious result. If we trace the words that white people in a northern community used in their newspapers, the same kinds of papers Bob Dylan pored over, we see that slavery actually declined as a keyword over time, that the word "emancipation" peaked early and then steadily declined (invoked mainly by Democrats attacking Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans).

By examining language in this disciplined form of visualization, we can glimpse the patterns that underlay Dylan's anxiety, his sense of the disconnect between the purposes of the war and the outcome of emancipation. But language alone is not enough.

Let's look at the work of another genius: Charles Minard. His map of Napoleon's March on Moscow. created in 1867, just when the black days of the Civil War were lifting from the United States, shows this elderly man reflecting, like Dylan, on a costly and haunting war from his nation's past.

Minard's graph is not unlike a written narrative. It gathers its power from being read in one direction; it carries one purpose. People have manipulated Minard's graphic in multiple dimensions, animated it, colorized it, and copied it, but it remains what it is: a graphic hat reduces a complex set of phenomena to a single plane. In fact, it is admired precisely for this act of concision, this concatenation of various data points into a single story of the diminution of Napoleon's army by weather, landscape, hunger, and the war. It presents, in the most abstract way imaginable, the deaths of 300,000 French soldiers in a struggle in which nearly a million people, soldiers but even more civilians, died.

In many ways, in other words, Minard's graphic has exactly the opposite effect of Dylan's. Minard contains history while Dylan sees history alive in his own life a hundred years later. They both give us something precious; might they be combined? Let's pull the camera back a bit and think about visualizing history.

Every work of history is, like a map or a story or a work of art, a projection, meant to make time discernable and comprehensible, just as a Mercator projection or a painting using perspective are necessary distortions. Just as a map's purposes can be discovered by the kind of mathematical distortion it employs, so can those of history.

If we let ourselves, we could become overwhelmed by how lost we are in time. If we were as confused by our position in physical space as we are about our position in the flow of time, we would be deeply concerned. It is not for lack of trying to get our bearings. Millions of people go to historic houses, battlefields, and the like because those places promise to provide one more coordinate in the very blurry map of the past in their heads.

That is a good strategy, since time and space are closely intertwined. When we try to picture the passage of time we have to plot it in physical space to see it; time, like wind, is invisible and can only manifest itself it its effects on people and places. To remember when we were, often we have to remember where we were. And to think about a past larger than our own personal history, we need to call upon the same strategies of triangulation we use every day.

In our personal memory we file away sets of coordinates: this room and that argument, this smell and that school hallway, this corner and that song on the radio. To "remember" the collective past we use what Eviatar Zerubavel calls "time maps" in our heads. Whether we are imaging the story of our family, our town, or our country, we fit things into a few precut patterns: "linear versus circular, straight versus zigzag, legato versus staccato, unilinear versus multilinear," with general plots of "progress," "decline," and "rise and fall." Looking back, we cannot help but think of watersheds and forking roads. As Zerubavel puts it, "History thus takes the form of a relief map, on the mnemonic hills and dales of which memorable and forgettable events from the past are respectively featured. Its general shape is thus formed by a handful of historically 'eventful' mountains interspersed among wide, seemingly empty valleys in which nothing of any historical significance seems to have happened." We build metaphorical bridges to close the gap between the past and ourselves, to hold things together.2

Professional historians build on this native ability to create ever more detailed maps of the past in their heads. The more coordinates we can have, the better. The parts of the time landscape I know well are detailed, full of familiar landmarks, places I can zoom down into and then back out of see to see larger and larger patterns, like a shot from a satellite. I can see, in my mind, processes unfolding, things connecting and branching and stopping. We also map the historical literature in this way, seeing its tributaries, its gathering, and its diffusion. Historians, it seems, don't have lists of books in our heads, databases of footnotes and citations, but instead an information landscape with its own peaks and valleys, streams and lakes.

What if we made this kind of expert knowledge visible and shared it with others? Visual and spatial patterns of the past will help us to understand the past in more subtle, complex, and thus more accurate ways, just as they help us understand nature. Though everyone has maps of time in their heads, many of those are of limited utility. Driving from Maine to San Diego, for example, we could just draw a big red line from one place to the other, Minard-like, connecting the two end points, and the map would not be "wrong." Neglecting to mention, however, the Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the desert in between would fail to give an adequate sense of what the trip will be like. Mapping the past is like that as well. We often draw a big red line from secession to the Emancipation Proclamation, say, telling ourselves that the beginning point and the ultimate destination were connected in an inevitable way, but that would neglect to mention all kinds of detours, decisions, and surprises in between that made the journey seem anything but straightforward or certain. History never travels as the bird flies; history walks across a varied and landscape of time.

Weather maps provide another analogy. Mark Twain said that climate is what we expect, but weather is what we get. We have to understand the historical weather if we want to understand why people did the things they did. That weather changed relentlessly, unpredictably. Even with our satellites and computers, we're still not very good at predicting weather, but we are great at analyzing it after the fact. We know where the hurricanes ending up hitting and can retrospectively understand how these complex processes unfolded. In a similar process, we can comprehend the historical weather, tracing where the currents led, how the storms brewed, and how the unpredictable somehow came to pass.

The beauty and utility of history is that time, that all-important fourth dimension in which we live, and of which we humans, alone of living things, are aware, can be mapped as it cannot be in our own lives. History is the only tool we have to even guess at where our location in time might be and where unpredictable winds and storms of history might blow us. New tools and new ways of thinking can help us get our bearings.

Every event of history unfolds in a spatial environment; history literally "takes place." Yet history, so obviously enacted in space and time, has not developed a rich tradition of spatial representation to clarify the relationships of space and time. In fact, our rich narrative traditions have generally relegated visualization to textbooks and heavy atlases in the reference sections of the library. The fact that historians' biggest visual hit is from 1861 tells you something important.

The great historian Fernand Braudel, in a lecture he gave to his fellow inmates in a German prisoner of war camp, described a fundamental fact about history: "An incredible number of dice, always rolling, dominate and determine each individual existence: uncertainty, then, in the realm of individual history; but in that of collective history . . . simplicity and consistency."3 Braudel would go on to found the Annales school, focusing on long processes and stable structures. But most historians don't like abstractions; we like concrete people, stories, and events. We see patterns as they are constituted of individuals and embodied in specific places and times.

So, let's go back to that haunting war and that question of freedom, to see if we might be able to "see" some pieces of history.

While the coming of the Civil War serves, often all too powerfully, as a lens that focuses all the events that come before, the post-emancipation period is more like a shattered mirror. There seems to be no clear beginning or end, no single event or no single place to focus. Every state followed a different path politically, and every locality had its own experience; each year differed from those that came before or after. And, it could be said, that every family, black and white, followed it owns path through these years, picking its way through the broken images and sharp edges of history.

Might we be able to see those paths? Might we be able to pick up the faint traces on the landscape? Might we be able to do something Minard could not do with the tools available to him: portray not merely group experience but also individual, family, and community experience? Might we be able to see, in other words, the historical weather?

My colleague Scott Nesbit and I have put together some glimpses of what we have in mind, tracing the paths of freedom forged by African Americans before, during, and after the Civil War, trying to see how freedom came out of the dark and evil days that so haunted Bob Dylan. This is challenging because the record of words is not as full as we would hope. We have to use every kind of strategy we can think of, use every kind of evidence we can find, to tell this complex and buried story. We've built most of our work out of the Valley of the Shadow Project, where we have a large database about the people, black and white, of Augusta County, Virginia, from the late 1850s to 1870, five years after the moment of freedom.

There, we can bore down to the stories of individual people and families. Doing so, we can see how people held in bondage created new lives for themselves: one of the great stories of American history, but one that been occluded by Gone With the Wind and our inability to see the ground.

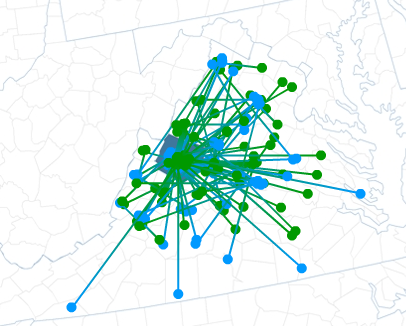

Let's look first at the patterns of marriage that recently freed people declared for themselves in the first moments of freedom. Stepping forward to the Freedmen's Bureau agent, these men and women announced that they had been married in the eyes of God if not in the eyes of Virginia. This map shows where the husband and wife in each couple had been born. Looking back from the first light of freedom into the darkness of slavery, we see a remarkable pattern: the husbands and wives had come from counties covering most of Virginia. A relentless domestic slave trade and widespread hiring out of slaves had moved people all over the state, pulling families apart, but sometimes giving them a chance to start. These couples often had children, sometimes as many as ten, showing that they had been able to hold their marriages together through all the trials of slavery and war. We see that emancipation came to people who had managed to create some kind of stability for themselves and their families.

On the other hand, we see how vulnerable newly free people could be. A heartbreaking brief letter from Isabella Burton captures it all: "Horace Bucker sold my two sons (seven & five years age) Benjamin & Horace, sold to Larke & Wright in Maddison County Va. Johnny Gilgarnett & Jeremiah Gilgarnett were playmates. I am living in Staunton Now a widow & alone, would like very much to see them." A glance at the population census for 1870, however, shows Isabella Burton living as a maid in a white household, her sons still lost.

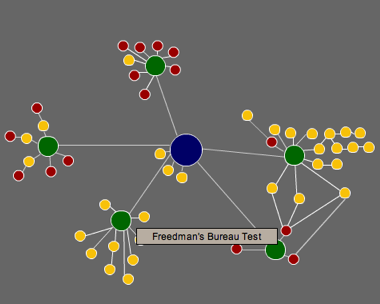

In the first years of freedom, African Americans used other means to create new networks and alliances. Look at the life of Aaron Shoveler, for example.

As you move the cursor over the circles [on the working map on the linked site] you can see the strategies he used to build a new life for himself. The cluster on the left shows Shoveler, a free black in Augusta in the 1850s, arrested for playing "fashionable" cards with another free black man and two slaves and reported in the newspaper. Shoveler disappears from the public record until the years after the Civil War, when, he suddenly appears in an array of activities. First, in 1866, he helps found a Methodist Episcopal church for black people, as the cluster to the far right shows. Then, as the cluster in the upper center reveals, Shoveler is elected in 1867 as a delegate to the convention in Richmond that will write a new constitution for the state of Virginia. In that same year, Shoveler testifies against the local Freedmen's Bureau agent, joining several members of his church. Three years later, he is elected an officer in the Freemasons.

While Aaron Shoveler's story was more fully documented than most, tracing this one individual shows the means by which African Americans created freedom out of very few resources. By examining the course of politics, of landholding, of church membership, and of family reconstitution we can see how individuals and families built new lives for themselves. [See additional maps.]

Remarkably, these are among the first maps historians have created of the process by which freedom was made. For over a century, we have relied on one map: David Barrow's sketch of his family's Georgia plantation in the late 1880s.

This map has been widely reproduced to tell one story about emancipation: formerly enslaved people remained on the plantations where they had been held in slavery but gathered as families in separate houses. But there was much more than this to freedom, as we have seen by looking at the stories of the married couples of Augusta County and of Aaron Shoveler.

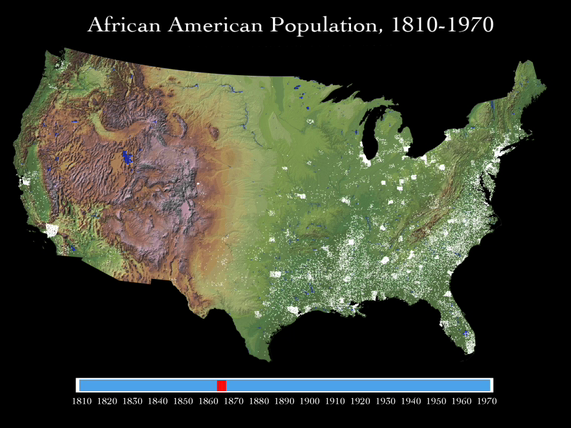

Pulling the camera back, we can see the results of such striving and activity across the South. By watching the process unfold over the course of the nineteenth century, we can see simultaneous movement to the south, the north, and the west, to countryside and city, especially after the moment of emancipation.

Each one of those golden dots held thousands of stories and we have only begun to glimpse them.

These glimpses into the ways that we might be able to picture the process of freedom show us that it will take us a while to figure out hoe to write or project or narrate or dramatize history from these sources. It will happen, however, and it will be interesting.

Changing the basis of our approach to the vast archive of the humanities creates productive tension. Exposing my language-based discipline of history to the visual, the graphic, and the dynamic throws it off balance. And that's exactly what the humanities, like all academic disciplines, need to do if they are to stay alive and vital.

1 Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 84-86.

2 Eviatar Zerubavel, Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past (University of Chicago, 2003), 27, 40.

3 Quoted in Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (London: Verso, 2005), 4.