Essays

When Was Linearity?: The Meaning of Graphics in the Digital Age

More even than her voice, and ours, among

The meaningless plungings of water and the wind. . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ramon Fernandez, tell me, if you know,

Why, when the singing ended and we turned

Toward the town, tell why the glassy lights,

The lights in the fishing boats at anchor there,

As the night descended, tilting in the air,

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night.

Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon,

The maker's rage to order words of the sea,

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins,

In ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds.

Prologue: "Emblazoned Zones and Fiery Poles"

After a lecture I gave at the Pauley Symposium on "History in the Digital Age" at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, in 2006, I was asked the following, profoundly felt question from the audience by the historian Tim Borstelmann:

I'm deeply concerned about the digital age that we live in . . . as a scholar, as a teacher, and, in addition, as a parent. . . . In this extraordinarily visualized culture that we operate in, I'm concerned about what is being lost. I should just say, by way of comment, I'm no Luddite at all; I live on the Internet like the rest of us. But I worry about exactly what is being lost in the ability to think logically, especially among our students. I'm concerned about what this suggests about the future. [I think about] the book Amusing Ourselves to Death [by] Neil Postman . . . which was an extraordinary indictment of the culture of television as a logico-historical development that has reduced our ability to think in a logical, linear fashion, that has essentially reduced us (though he was too nice to put it this way) to idiots. If he were still alive and able to update Amusing Ourselves to Death, [his argument] would be emphatically more clear [amid] . . . the culture of the internet.2

My answer was the seed for the present essay. I broke the line of my questioner's thought—to the audience's initial surprise—by valuing non-linearity instead:

Let's imagine that a hundred and fifty to five hundred years from now some parent says to their kid: "I'm concerned that you'll lose the talent for modular and loosely coupled knowledge, the ability to quarantine your concerns and issues in object-oriented modules that can project an image of emancipation. What do we want in the world, after all? It's just not true that we only want information to be free. We want people to be free. I hate to say this at a history conference, but part of what such emancipation has always meant is that people should be free to choose either to commit to, or to be emancipated from, their history. To be emancipated from history means to have the maneuver to be able to break off the relationship with a whole linear sequence of events, contingencies, and people—to be a free-floating packet of modular information. So I can see in the future that we might have the same dread of losing non-linear freedom that today we have of losing the freedom that was linearity.3

The present essay is an attempt to complete this line—which is to say non-line—of thought.

Doing so will require challenging linearity with an alternative framework of thought that is not just negatively defined (non-linearity, as Borstelmann and I conceived it in our exchange) but positive in its own right, big with its own traditions and ways of thinking. The framework I propose (foreshadowed by Borstelmann as our "extraordinarily visualized culture") is graphics.

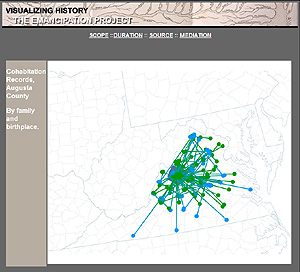

Figure 1. Map diagram from The Emancipation Project, ed. Edward L. Ayers and C. Scott Nesbit, Virginia Center for Digital History and University of Virginia, retrieved 1 August 2008, http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/emancipation/ (Click on images for larger versions)

After all, one of the signature features of modern thought has been the rising importance of graphical knowledge—to the point, for example, that in the sciences and social sciences what might be called tiered graphics (conceptual schemas built up from visual diagrams, which in turn rest on data tables, graphs, maps, and other lower-level graphical structures) are often instrumental to, if not constitutive of, knowledge. Even the humanities, though traditionally text-centric, are now going graphical. The Pauley Symposium mentioned above, for instance, showcased projects by Edward Ayers, Peter Bol, and Robert Schwartz that apply geographic information systems (GIS) to the study of history. The primary output of such systems is the visual rendering of data points over maps (figure 1).4 Similarly, one of the most influential books of literary criticism in recent years has been Franco Moretti's Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (2005), whose method of "distant reading" discovers macro-patterns and cyclical developments by processing large datasets of literature (e.g., thousands of novels published over many decades) through analytical diagrams and maps (figure 2 [permission to reproduce images pending]).5 Moretti's commentary focuses on these abstract graphics, which in effect become works of wonder and mystery in their own right substituting for the now invisible works of primary literature.

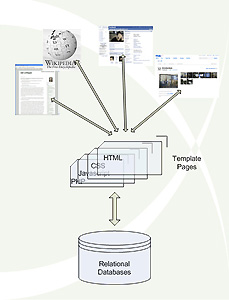

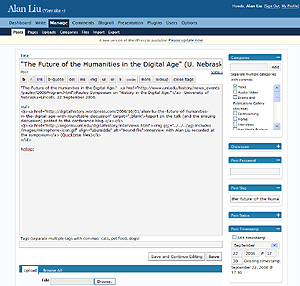

Meanwhile, digital technology has accelerated the graphical trend. Digitally-generated designs, diagrams, graphs, slideshows, maps, photographs, animations, video, and so on are now effectively the lingua franca of knowledge. Consider the presentation of knowledge, for example. When specialists today communicate their findings to others in their field, let alone in other fields, they make PowerPoints (or Web presentations) studded with bullet lists, graphs, diagrams, etc.—spectacle shows that (like the diagrams in Moretti's book) become the de facto primary object of knowledge. Audiences are increasingly asked to ponder visually powerful or intricate slides whose condensed knowledge a presenter can only sketchily gesture toward, as if to say, "There it is! What more needs to be said?" In regard to the underlying production of knowledge, the case is even more compelling. Whether we think of professional or public knowledge today (on the one hand, for example, researchers working on collaborative online documents; on the other, so-called collective intelligence or the wisdom of the crowd posting Web 2.0-style to Wikipedia), very little meaningful work can occur in contemporary digital environments without the coordination of input and output through "graphical user interfaces" (GUI), middleware "templates" (manifesting in visual designs), and server-side database tables (represented not just in SQL code but in table-relation diagrams).6 It is this congeries of graphical devices that allows content-producers of whatever technical proficiency to work adeptly with contemporary computer programs (figure 3).

Figure 3. Editing interface for WordPress, a popular content management system/blog engine, showing the graphical user interface typical of contemporary software applications (updated in Web 2.0-style applications such as WordPress with a variety of functions for controlling front-end presentation , the back-end database, and the CSS or style-sheet defined templates that intervene in between).

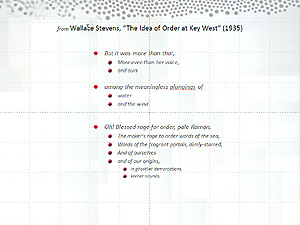

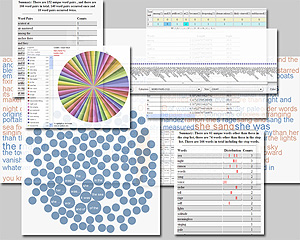

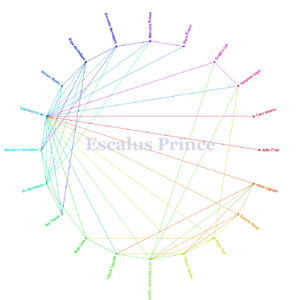

An illustration will punctuate the point. Consider a normal object of humanistic inquiry such as a poem. Specifically, consider Wallace Stevens' "The Idea of Order at Key West" (1935), which I choose emblematically because—in answering the "meaningless plungings" of modernity with an orderly vision of "emblazoned zones and fiery poles"—it in fact prophesied the rising tide of graphics that eventually led to postmodern, non-linear knowledge. How can we today best "read" this poem? Harvesting the lessons of the GIS-historians, Moretti, and the new digital technologies, we might follow a procedural script as follows.7 First, transform the poem into a dataset by using any standard text-analysis algorithm (such as the word-frequency, word-distribution, and word-pairs programs available through the online TAPoR text-analysis portal).8 Then, pipe the dataset through any of today's sophisticated graphics or mapping algorithms (such as the word-tree, bubble-chart, stack-graph, matrix-chart, and word-cloud generators available through the IBM Visual Communication Lab's Many Eyes portal) (figure 4).9 Or, more simply and playfully, just make Stevens' poem into a PowerPoint slide, whose bullet list—to foreshadow argument to come—is only at first glance monographically linear (figure 5). It is actually an elegantly minimalist expression of today's normative form of knowledge: the multigraphically networked (e.g., a "tag cloud" or "social graph" in which data from many hands appears as a network of nodes) (figures 6, 7).10

Figure 4. Stevens' "Idea of Order at Key West" processed through TAPoR text-analyis tools and IBM Many Eyes data-visualization tools

Figure 6. Tag cloud of Wallace Stevens’ "The Idea of Order at Key West" generated by feeding the excerpt quoted at the beginning of this essay into the Wordle tag-cloud generator (http://wordle.net/).

Figure 7. Social graph of the characters of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet created by students in an undergraduate course using the Facebook Friend Wheel application (http://thomas-fletcher.com/friendwheel/).

This essay poses the puzzle: what is the relation of linear (written) to graphical (digital) knowledge today? Which is truer? Or, to follow up on my Pauley Symposium response, which is freer?

From Linearity to Graphics: A Tale

Old habits die hard, of course, and it is hard to think about the relation between linear and graphical knowledge in a written argument such as the present without immediately spinning linear tales about that relation. I am already guilty, having sketched a modern-to-postmodern line of development in my example from Stevens above. So, before going on, it may be useful just to light the fuse of linear argument and let it burn out all at once. In particular, let me tell a tall tale of the historical transition from linear to graphical thought that rehearses—and so prepares us to exorcise—the now already clichéd debate between those who mourn the loss of linearity and those who celebrate the new hypermedia. Maybe then we can think more flexibly about the issues.

Here, then, is a variation of the usual linear history—i.e., fairy tale—of how we got from modern, linear rational thought (Enlightenment or twentieth-century) to postmodern, digital graphical thought ("Once upon a time, there was an evil king named Modernism," etc.). The first chapter of our tale goes back at least to the 1930's. My illustration above—a Wallace Stevens poem from 1935—is also exemplary because, in his job as an insurance executive, Stevens was not just a poet but one of our original knowledge-worker poets. It was precisely in the 1930's, after all, that the new middle class of salaried knowledge workers raced ahead at six times the demographic growth rate of wage workers.11 As it were, modern poet: he who numbers meters and actuarial tables, the unacknowledged knowledge worker of the world. Indeed, the example of actuarial tables is key. What were the meaningless plungings Stevens referred to in his poem about the modern order ("The meaningless plungings of water and the wind")? In a general sense, of course, it all had something to do with World War I, breakdowns in established belief systems and institutions, social and cultural mobility, mass media, etc. But in the context of a modern insurance company and all its ilk, meaningless plungings had specific communicational forms that were the producer's complement to the new mass-consumer media of the time. Paradoxically, these forms were at once meaningless and ultraorderly—a sort of systemized meaningless plungings. I refer to the dreaded file, form, table, memo, and report—i.e., the entire, new discursive regime that JoAnne Yates has studied in her Control Through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management (1989).12 By contrast with older stack-file systems, for instance, the new "vertical file" was all about random, non-linear access (figures 8, 9). So, too, new business-correspondence systems designed by William Henry Leffingwell applied Taylorist "scientific management" principles to make office routines consummately non-linear (e.g., systems for assembling letters from boilerplate paragraphs indexed by arbitrary codes).13 Such is the genealogy of all the non-linear forms and tables—including actuarial tables (figure 10)—ancestral to today's graphics. They were the programming media for a modern, scientifically-managed system of work that resampled and reshuffled traditional task sequences for efficiency—even if, ironically, the fate of such non-linear restructuring was submission to a new, modern linearity: the Fordist assembly line.

Figure 8. An illustration of how difficult it was to locate correspondence in press books and letter boxes. Catalogue for Yawman and Erbe, "Rapid Roller Letter Copier," 1905, Hagley Museum and Library). (Reproduced, with this caption, in JoAnne Yates, Control Through Communication, p. 38)

Figure 9. "Alphabetically organized vertical files with the requisite equipment." Catalogue, Hoskins Office Outfitters, Philadelphia, ca. 1912, Hagley Museum and Library. (Reproduced, with this caption, in JoAnne Yates, Control Through Communication, p. 60).

Figure 10. Actuarial Table (IRS Publication 939 on Pensions and Annuities) (http://www.irs.gov/publications/p939/ar02.html).

Reacting critically against such programmed mass-producer and mass-consumer society, the modernist avant-garde sensibility expressed in Stevens' poem—however complicit it might have been with the insurance-company new world order—drew a proverbial line in the sand. Thus far shall the tide of systematized meaningless plungings rise, it said, and no farther. The "emblazoned zones and fiery poles" that Stevens casts over the sea were a kind of imaginary redemption of the grid lines in a modern actuarial table.14

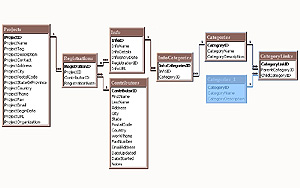

The second chapter in our tale then brings the argument forward to postmodernism/postindustrialism. Of course, in one sense it is not much of a jump at all from early or mid twentieth-century knowledge work to the coronation of such work today, when—as Robert B. Reich wrote in 1991—the "work of nations" is dominated by the "rise of the symbolic analyst."15 Today's knowledge workers are extractors, manufacturers, transporters, and marketers of symbolic rather than physical capital. But they also manage, or are managed by, a new sea of "meaningless plungings." That sea is information—especially the Internet, in which (to use the standard metaphors) we navigate, surf, and drown. In a fuller study, we would want to investigate the surface forms of today's Web 2.0 (e.g., blogs, wikis, social-networking sites, and other collective, decentralized platforms of "meaningless plungings"). So, too, we would want to reflect on the undergirding "middleware" that circulates data convectionally into those surface forms (e.g., through template pages operated by PHP scripts in tandem with CSS/XHTML tags). Finally, we would want to consider the networking protocols that conduct data laterally around the world (e.g, TCP/IP and the whole architecture of routed, packetized communications).16 But, to be brief, we can take the measure of the whole by plunging down through all the networking levels to the information-management systems increasingly at the bottom of it all (for a summary diagram of Web 2.0 data architecture, see figure 11). I refer to the so-called deep web of databases—particularly, relational databases. First theorized by E. F. Codd in 1970 at IBM, relational databases such as MySQL or SQL Server now undergird everything from corporate knowledge systems serving up customer orders to Wikipedia, WordPress, Facebook, MySpace, Flickr, Digg, Google Earth, and other Web 2.0 applications serving up posts, comments, friends, maps, and ads.17

I have elsewhere attempted a humanist's summary of relational database theory.18 The bottom line is that the relational database was designed to be exactly non-linear. Earlier database architectures (e.g., "hierarchical" databases) traversed computational pointers sequentially through logical trees and/or physical memory structures (like telling someone how to find a book by taking the elevator to the fourth floor, turning left, going to the twelfth aisle, walking down five shelves, etc.). Codd's innovation was to do an end-run around both logical and physical data dependency via an architecture of "atomic" information. In his design, each datum (held in separate database fields labeled, for instance, "customer_id," "first_name," "last_name," "street_address," "book_isbn," "credit_card_number," "date_of_order" etc.) is related to others not through lines of association but through on-the-fly, mathematical operations (specifically, set-algebra operations formalized in the select, union, intersect, join and other functions of Structured Query Language [SQL]).19 To take a cue from Stevens' mythopoeic tone, we might say that a new god of random access thus arises for whom creation means returning to a primal state—now entropically modern rather than classically protean—where any one atom can be free to mix with any other in non-linear, undetermined order.

But, in another sense, postmodernism/postindustrialism is not just more meaningless plungings operated with better machinery. It is a changed attitude toward those plungings. Until recently, that difference might have been adequately stated in poststructuralist (Barthesian or Foucauldian) terms as the death of the author.20 But, after the triumph of business teams, Web 2.0 collective intelligence, and—sponsoring the whole horde—globalism, authorship is more than ever in demand even if it is now conceived as collaborative rather than as a solo act of genius.21 This is why the premium today is on the post-industrial successor to authorship: design. Just twenty or so years ago, the most creative students wanted to be authors or artists. Now they all want to be "designers" working in teams to create software, Web sites, games, clothes, cities, houses, art, environments . . . whatever. Given the new paradigm of everyone co-designing/co-authoring everything together, the controversy has retreated from authorship to a last-ditch battle line: linearity itself, the underlying monographic line of thought that is the stripped-down version of authorial identity (in recent parlance, a "brand").

Today, the debate is about a perceived loss of faith not just in the possibility but in the very ideal of linear thought. Linear fundamentalists still argue for old-school rigor. Writing for a public audience (in the Los Angeles Times), for example, Michael A. Hiltzik opines:

[Some] contend that, as a fresh new medium, the Web eliminates the need for such quaint devices as linear thought or the telling argument. Why think in straight lines when as a user you can veer willy-nilly from subject to subject, aperçu to aperçu, with no more effort than it takes to move a mouse?

Unfortunately, there are a few problems with this argument. Schoolteachers all over the country already see their Web-savvy students having trouble stringing sentences together coherently, probably because the process demands more intellectual subtlety than bopping from site to site. . . .22

But, clearly, the tide is flowing toward non-linearity. Thus Scott Karp (former Director of Digital Strategy for the company that publishes The Atlantic) is typical of the swarm who today champion all things open-source, wikified, socially-networked, mashed-up, and—the very signature of what might be called cyberlibertarianism 2.0 (i.e., the hype over Web 2.0 that began after the dot.com bust ending the first era of entrepreneurial cyberlib)—anti-linear.23 Writing in his Publishing 2.0 blog, Karp comments:

What if I no longer have the patience to read a book because it's too . . . linear.

We still retain an 18th Century bias towards linear thought. Non-linear thought—like online media consumption—is still typically characterized in the pejorative: scattered, unfocused, undisciplined.

Dumb.

But just look at Google, which arguably kept our engagement with the sea of content on the web from descending into chaos. Google's PageRank algorithm is the antithesis of linearity thinking—it's pure networked thought.24

Meanwhile, academic theorists of new media (and theorist-artists in the academy's MFA orbit), also vote non-linear, even if they are more carefully neutral or scholarly in their phrasing. Thus, amid her otherwise fierce, uncompromisingly anti-linear argument in "Stitch Bitch: The Patchwork Girl" (1997), Shelley Jackson finesses: "I have no desire to demolish linear thought, but to make it one option among many."25 Similarly, but with a Cold War spin subtly different from Jackson's classically liberal formulation, Lev Manovich speaks the language of détente. In a well-known section of his The Language of New Media (2001), he declares databases and linear narratives to be "natural enemies." But, then, while ceding the main territory to databases, he says diplomatically: "A traditional linear narrative is one among many other possible trajectories [drawn over a database], that is, a particular choice made within a hypernarrative."26

Not accidentally, we notice, the non-linear camp goes graphical to clinch its case. This is because graphics—as in standard representations of table relations in a database (figure 12)—are today functionally the most intuitive representation of databases, networks, and similar structures. For example, it is hard to find position papers on Web 2.0 that do not commit the visual cliché of a tag cloud or social-network graph.27 So, too, Jackson's best-known work of hypertext literature, Patchwork Girl (1995) was written in the Storyspace program, which visualizes hypertext through graphics (index-card-like boxes on the screen linked to other boxes) visible not just to the author but to the reader.28 And, in the same vein, Manovich begins his The Language of New Media with an image-dense discussion of Dziga Vertov's modernist experimental film technique as if graphics were the sine qua non of the language of new media.29

To reprise: once upon a time (as recently as modernism) there was linear thought. But now—a happy or unhappy ending depending on one's view—we have passed a point of no return beyond which one idea of order has undergone a sea-change into another. We have moved from linear thought to graphics, modernity to postmodernity, and knowledge to knowledge work. Indeed, this last phrase, knowledge work—one of the greatest clichés of postindustrialism—is worth pondering. Is pushing numbers and words into a database knowledge? No one today knows, however much we can all see the result (to use the verb that organizational ethnographers such as Shoshana Zuboff hear so often in interviews with workers in computerized firms who say such things as, "with the data-base environment, there is one information system for all to see . . . You can see the whole . . . a helicopter view" ).30 That is why we call it "knowledge work," the work part of which business books discuss so amply with the aid of organizational diagrams, process flowcharts, bullet lists, and other visualizations even as they spend zero time on the apparently unknowable and undiagrammable nature of knowledge as such.31

When Was Linearity?

But wait. I cast the above historical tale in the mode of fable, of course, because it doesn't really bear up to close inspection. Linear to non-linear, monographic to multigraphic, textual to visual, etc.—any way we formulate it, the apparent binary that frames a linear history of transition from modern linear/written thought to postmodern/digital thought is messy. There are too many moving parts, and they do not all align. Linear vs. non-linear, for example, is not actually homologous with textual vs. visual, since innumerable instances of non-linear text and linear visuals scramble the circuits. Most fundamentally, graph lies at the undecidable etymological root of both linear graphemic writing and multiaxial graphics.32

So, to get the story right, we will have to have to do some due diligence (like doing a title search before buying a house). Actually, when was linearity? McLuhan said it started with Gutenberg. Shifting our beginning point just a bit earlier to be sure we catch it all, we can say that linear thought supposedly spans the continuum of late-medieval, Gutenbergian, Albertian, Cartesian, and twentieth-century epochs that together constitute long modernity (i.e., civilizational modernization). But rather than just endorsing that argument, we should ask diligently when it all really happened. Such care is necessary, it turns out, because on close inspection linearity seems to be relatively recent. It is so recent, indeed, that it may not have existed historically at all. Research in anthropology, history, history of the book, and media archaeology now suggests that, during the long millennia leading up to (and through) twentieth-century modernism, thought, discourse, and media did not cleave to lines of thought.

To start with, consider primary oral cultures, by which scholars of early media such as Walter Ong mean prehistorical societies in which, whether or not writing was known, most people were illiterate, the literate themselves thought and composed orally, and legal, political, and other official transactions were all spoken and heard. Beginning with Milman Parry's discovery of the oral nature of Homer's epics, researchers have shown that primary oral cultures simply did not have a notion of linear discourse.33 Instead, discourse followed a jumpy, mobile, dynamic protocol centered around local nodes of attention tailored to the severely restricted attention-economy that the ancients called kairos (opportunistic, seize-the-moment time) and that cognitive psychologists today call working memory (transient memory).34 Commonplaces, topoi, proverbs, set pieces, conventional encomia, formulaic images, and other dicta were standard. As they said, "a stitch in time saves nine" (though they also said, "measure twice, cut once")—where the scale of kairotic cognition was indeed on the order of the local stitch (or even half-line hemistich) of the oral, bardic poem.

Such stitch-at-a-time order, of course, is not order at all in the sense of a line of thought. Indeed, as tested empirically upon primary oral cultures that have survived into modernity (e.g., among South Slavic peoples), living bards who claim to recite linearly word for word have an entirely premodern notion of what linear sequence means. Audio recordings of their performance show that word for word actually means improvised substitutions, transpositions, and other circulations of material ranging in scale from the shuffling of metrically equivalent phrases to the recasting of whole episodes.35 It is as if every sentence can be said in many ways. In many ways can every sentence be said. Truth is to be found in many sayings.

Now consider the case of early literate cultures prior to print. At first glance, the invention of writing on clay, papyrus, and parchment might seem to have decisively impelled orality toward linearity. It did so by means of the list. As anthropologists such as Jack Goody have argued, lists were not a feature of orality but were original to writing.36 This is because writing arose not for such later purposes as philosophy, theology, memoirs, fiction, and so on (i.e., literature in the general sense) but instead for accounting. At the primordial origin when literacy and numeracy were still one, the essential message was of the sort: "twenty bushels of grain paid by John the farmer in taxes to the king; fourteen bushes of grain paid by Thomas the potter in taxes to the king." For example, the following inventory of fourteenth-century BCE tablets recovered at a Syrian port is dominated by lists in the category of "administrative, statistical, business documents":

| Categories of Writings | Number of Instances | ||

| 1. Literary texts | 33 | ||

| 2. Religious or ritual texts | 31 | ||

| 3. Epistles | 80 | ||

| 4. Tribute | 5 | ||

| 5. Hippic Tests | 2 | ||

| 6. Administrative, statistical, business documents: | |||

| I. Quotas (conscription, taxation, obligations, rations, supplies, pay, etc.) | 127 | ||

| II. Inventories, miscellaneous lists and receipts | 28 | ||

| III. Guild and occupational lists | 52 | ||

| IV. Household statistics and census records | 6 | ||

| V. Lists of personal and/or geographical names | 59 | ||

| VI. Registration and grants of land | 16 | ||

| VII. Purchases and statements of cost or value | 5 | ||

| VIII. Loans, guarantees and human pledges | 7 | ||

| 7. Tags, labels or indications of ownership | 18 | ||

| 8. Other | 3137 | ||

But, on second glance, linearity clearly cannot be ascribed to such primaeval PowerPoints at the dawn of writing. In actuality, the list form was anything but meaningfully linear. In this regard, early historiography or history-writing is revealing. Hayden White has directed our attention to annals historiography, which was organized in the form of chronological lists. In such annals, chrono-logic is a vertebral column of linearity so flensed of anything we would today recognize as logic that it is hardly recognizable as linearity at all as opposed, for example, to multilinear hypertext. The following is an excerpt that White takes from the Anglo Saxon Annals of Saint Gall:

| 709. | Hard winter. Duke Gottfried died. |

| 710. | Hard year and deficient in crops. |

| 711. | |

| 712. | Flood everywhere. |

| 713. | |

| 714. | Pippin, mayor of the palace, died. |

| 715. 716. 717. | |

| 718. | Charles devastated the Saxon with great destruction. |

| 719. | |

| 720. | Charles fought against the Saxons. |

| 721. | Theudo drove the Saracens out of Aquitaine. |

| 722. | Great crops. |

| 723. | |

| 724. | |

| 725. | Saracens came for the first time. |

| 726. | |

| 727. | |

| 728. | |

| 729. | |

| 730. | |

| 731. | Blessed Bede, the presbyter, died. |

| 732. | Charles fought against the Saracens at Poiters on Saturday. |

| 733. | |

| 734.38 | |

Here, chronology certainly seems to assert linear order, even to the point of recording null years when apparently nothing happened. But what meaningful line of thought is inscribed in such order? Are we reading a dynastic narrative of kings and civilizations ("Charles fought against the Saxons," "Saracens came for the first time")? Are we reading instead a tale of local regimes ("Duke Gottfried died," "Pippen, mayor of the palace, died")? Or, dissolving all political event in a circumambient, agricultural world view, are we instead just witnessing a seasonal tale of crops ("Hard winter . . . Hard year and deficient in crops . . . Great crops")? The answer, as best as we can tell, is all and none of the above. The lines of thought shoot off in multiple directions and on multiple levels.39

Nor is it just the list form that shows the equivocal nature of linearity during early literacy. If we concentrate on the portion of the Christian epoch that takes us from the first centuries of the church through approximately the thirteenth century (a span whose mid-point is marked by the Annals of Saint Gall instanced above), we discover a dramatic innovation in media culture that turns out—despite its recent reputation—to have cut exactly against the grain of linear discourse. I refer to the rise of the codex book (today's normative book with separate, cut pages), whose adoption contra the classical and Jewish scroll helped define the identity of Christianity (and which has lately come in for increased attention by scholars of historical media because, as witnessed by Roger Chartier, Peter Stallybrass, Jerome McGann, or Johanna Drucker, its relation to recent digital media grows ever more unpredictable and interesting the more we look into it).40 Many reasons have been suggested for the dramatic break that Christians made with pagan and Jewish scroll culture when they gave to the codex—previously used for casual, transient, notebook-style discourse—all the cultural authority of the older rolls. Codices were more portable, could be secreted on the body, could contain more material, could assemble a variety of texts, were identified with the lower-middle class people who first adopted Christianity (accustomed as they were to using notebooks for practical accounting, lists, letters, etc.), asserted a symbolic difference from Jewish culture, and so on.41 Whichever combination of reasons is true, the result—as Stallybrass has argued in his important essay, "Books and Scrolls: Navigating the Bible" (2002)—is that Christian discourse was profoundly non-linear.42 Unlike scrolls, which had to be written and read linearly by rolling and unrolling, codices facilitated non-linear writing (e.g., compiling multiple texts in the same book) and random-access reading (e.g., cross-reading the four Gospels with the aid of concordance, bookmarking, finding, and other organizational or layout devices). Indeed, the more advanced codex culture became, the more elaborate grew its gadgets for non-linear reading. As Stallybrass notes,

In the thirteenth century, . . . all sorts of navigational aids were produced for preachers and university teachers: biblical concordances, subject indexes, library catalogues. Reference tools increasingly followed an alphabetical system (like modern indexes), rather than a hieararchical ordering. . . . Manuscripts were given numbered folios or openings, and arabic numerals were increasingly used. The bible and other books were divided into chapters (43-44).

The evidence, as Stallybrass concludes, demonstrates "the long history of Christianity in the creation of systematic methods of discontinuous reading. . . . The codex and the printed book were the indexical computers that Christianity adopted as its privileged technologies" (73-74).

I single out Stallybrass's article from among the larger body of research that might be cited not just because it puts the case strongly but because its central exemplum links the experience of the codex to that of lists—specifically, to that of the chronological annals I earlier mentioned. Stallybrass's focal exemplum, of course, is the Bible, the great codex that must loom large in any analysis of Western reading practices in the first 1.8 millennia or so. How did one read the Bible (or have it read/sermoned to one)? The gist of Stallybrass's argument is as follows. By and large—with only the exception of some Protestant reading methods that might have been honored more in principle than in reality—one read the Bible in daily doses regulated institutionally by the chronology of the liturgical year. In principle, the calendar of that year, starting on January 1, would coincide with a linear reading of the Bible starting with Genesis. But, in practice, even the most determined Protestant attempts to rescue the Bible from Catholic liturgy (which, as Stallybrass notes, required using multiple fingers and bookmarks to collate discontinuous passages from a remarkable number of separate locations in a missal) ended up slicing and dicing the good book. This is because chrono-logic is not in fact linear but instead annals-like in its conjunction of multiple agendas, levels, interests, heritages, etc. Therefore, as Stallybrass instances, it was very inconvenient that the liturgical reading of "Genesis chapter 1, verse 1, Matthew chapter 1, verse 1, and Romans chapter 1, verse 1" had to be pushed back to January 2 because January 1 was reserved for the Feast of Circumcision, which remembered that "Christ was a Jewish boy"; or, again, that "the end of the year was disrupted by a series of feast days which had been preserved and which each had its own special readings" (49). In sum, despite "the Church of England's attempt to produce an 'orderly' (i.e., sequential) reading of the bible, the crucial point remains that there were innumerable exceptions (including Sundays and feast days, the very days when the congregations were largest). And, of course, the service still depended on flicking back and forth between the Jewish scriptures, the Gospels, and the Epistles" (50). At best, Stallybrass reflects, the codex accommodated "the combination of the ability to scroll with the capacity for random access" (42). Realistically, the codex was "a technology of discontinuity" (73).

So now we come to the decision point that might be called the Big Bang of our quest for the origin of modern linear discourse. After canvassing oral and early literate cultures, the stakes have been raised terrifically high for the next turn of events: print culture. Every epoch along the way seems to have been either a-linear or, at best, only very equivocally linear. This corners us into a stark dilemma: either linear discourse arose in a mysterious Big Bang at the moment of the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century so as to cancel the non-linear bias of earlier epochs, or, skeptically, it never arose at all. Which way does the evidence lead?

It would be narratively fulfilling at this point to be able to agree with McLuhan (a Big Bang thinker if ever there was one) that the invention of print suddenly initiated modern linearity. According to McLuhan, print literacy created modernity in the image—specifically, the monoaxial graphemic image—of linearity:

Literacy propelled man from the tribe . . . and replaced his integral in-depth communal interplay with visual linear values and fragmented consciousness. . . . He begins reasoning in a sequential linear fashion; . . . The new medium of linear, uniform, repeatable type reproduced information in unlimited quantities and at hitherto-impossible speeds. . . .43

It was a direct line from there, in McLuhan's thesis, to the Enlightenment and, especially, to modern American thought of the sort Alexis de Tocqueville comments on in a passage discussed in McLuhan's "The Medium is the Message." "In America," de Tocqueville wrote, "all laws derive in a sense from the same line of thought. . . . One could compare America to a forest pierced by a multitude of straight roads all converging on the same point."44

But the problem with McLuhan's line of thought is that the more we learn from recent scholarship on the history of the book and the history of reading (fields whose vigorous growth was ironically inspired by McLuhan's media approach), the more controvertible print linearity seems.45 From the viewpoint of the history of the book, for example, it is thus inconvenient that the decisive intervention of the codex preceded moveable type, that the non-linear codex continued its hegemony, and that consequently, as Stallybrass observes, "one might want to see the invention of printing less as a displacement of manuscript culture than as the culmination of the invention of the navigable book—the book that allowed you to get your finger into the place you wanted to find in the least possible time" (44).46 From the related viewpoint of the history of reading, meanwhile, McLuhan's thesis was threatened to the core by the controversy that arose in 1970 when Rolf Engelsing in Germany advanced a counter-thesis. According to Engelsing, print in the Enlightenment—the supposed high age of linear rationality—invented the kind of mosaic, field-effect, or otherwise non-linear experience that McLuhan accounted to electronic media at the end of print.47 Leah Price paraphrases: "Toward the end of the eighteenth century, in Engelsing's account, the proliferation of new books gave rise to a model of 'extensive' reading—skimming and skipping, devouring and discarding" much different from earlier "intensive" modes of reading.48 And Chartier, referring to the same thesis, comments: "The 'extensive' reader, that of the Lesewut, the rage for reading that overtook Germany in Goethe's time, is an altogether different reader—one who consumes numerous and diverse print texts, reading them with rapidity and avidity. . . ."49 Such, we note, is not dissimilar to digital reading as Chartier understands it: "electronic textuality enables the development of demonstrations and arguments following a logic that is no longer necessarily linear or deductive. . . . It enables an open, fragmented, relational articulation."50

None of these counter-McLuhan arguments is a smoking gun, of course, since trying to deduce the so-called mentalité of the historical reader from material, formal, economic, and other obstinately non-mental past evidence is still far from an exact science.51 At a minimum, though, the counter-arguments establish that the evidence for linearity in the fabled golden age of modernity—the age of high print—is complicated. It is so complicated, indeed, that it will now be salutary, in the mode of due diligence, to take up Occam's Razor and try a simplifying thought-experiment. Of course, the danger of skeptical simplification is that it will have a deflating, reductive effect—like following the yellow brick line to the Emerald City only to discover that the Wizard of Oz isn't. But skeptical reduction is not the only possible outcome of our conceptual experiment. The trick is to wield Occam's Razor productively, generatively. Specifically, we want to ask what might be learned from a reductive simplification chosen purposely to be different from the previous reductionism of linearity.

Cutting the Line

When was linearity? The simplifying solution we should now entertain is that maybe linearity wasn't. In the face of unhelpful answers like this, of course, the generative solution is to unask the original question and ask a new question. Let me thus suggest a few counter-suppositions to the modern-to-postmodern tale I recounted above in order to provoke such a fresh question. Suppose that linearity is not a historical phenomenon to be verified through investigation of social, economic, religious, and other areas of cultural experience. Suppose also that linearity is not a psychological phenomenon (a "mentality") to be verified by research in the history of the book or the history of reading supplemented by cognitive psychology experiments performed on contemporary subjects. Of course, cultural and mental experience are obviously crucial to the puzzle. But to think that their felt reality is the actual phenomenon at stake when we debate linearity is a category mistake. The appropriate category of analysis is one that I earlier intimated in the name of "freedom" and that W. J. T. Mitchell takes up in regard to image-word (if not graphics-linearity) relations in his Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology.52 That category is ideology. Linearity never was historically or mentally because it was always only a critical way or ideology of thinking about what was. Therefore, the new question we should ask is: what was the ideological function of linearity? And, correlatively, what is the ideological function of contemporary, digitally-facilitated post-linearity as it knows itself under the sign of graphics?

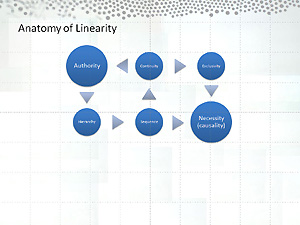

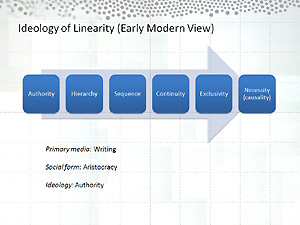

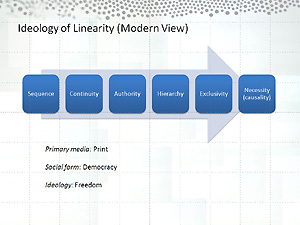

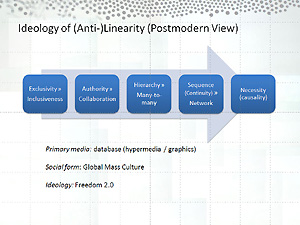

Enacting the graphical, let me sketch an answer through the following series of thought-images (originally created in PowerPoint):

The first is a conceptual diagram of linearity that is purposely non-linear (figure 13). The core of the hypothesis I propose is that linearity is not a single, integral concept—and certainly not one with any necessary internal linearity of logic. Rather, linearity is a mutable matrix of at least the following component values (with others that might be added in a fuller examination): authority, hierarchy, sequence, continuity, exclusivity (i.e., you're either in the line of succession, the mainstream, etc., or not), and necessity (or teleological causality). Exactly how these nodal values—the axiology underneath axial thought, we might say—align to create an impression of linearity depends on the dominant or emergent ideology in any epoch of modernization.

In what scholars now call the early modern (late medieval though renaissance) era, linearity was constructed through an alignment of values that looks something like this: authority → hierarchy → sequence → continuity → exclusivity → necessity (figure 14). The fine details may be debated, but the main point is that authority was king, and such other values as hierarchy, sequence, continuity, and exclusivity—with their attendant institutions, practices, and communicational forms—supported, channeled, reproduced, expressed, or otherwise rendered authority. The ultimate impression, as is true of any ideological formation, was historical necessity—as if God or nature itself locked reality into what the early moderns called a "chain of being."53 Such was linearity according to the ideology of authority. And the written word of this ideology (its primary medium) was its law. (The specifically modern quotient in early modernity had to do with the increasing destabilization of the chain-of-being world view in the renaissance, as witnessed, for example, in Ulysses' extended lament over the shaking of "degree" or "rule" in Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida).54

But now let's advance to modernity proper from the Enlightenment on (figure 15). In modernity, democratization (coupled to industrialization) redrew the line so that an abstract, rational notion of sequence (in unstable relation to continuity) came to the fore ahead of authority and hierarchy, however residually potent the latter values remained. It's like standing in a modern line or queue today: reason declares that you should be first because you got there first or because you merit first place, not because your parents were lords.55 The privileging of rational sequence—of the Cartesian line of thought—was the very reason that we (and McLuhan) now think of the Enlightenment as distinctively linear by contrast with the preceding early-modern era, whose aristocratic linearity (e.g., disturbed lines of succession created through dynastic usurpations or mergers) now seems to us bizarrely non-Euclidean. Of course, the ultimate impression was still historical necessity, which the Enlightenment called progress. Whether continuously ameliorative in the mode of William Godwin's improveability of man or violently discontinuous a là the French Revolution, linearity was reconstructed according to the new ideology of freedom.56 Arising as an ideological critique of feudal times, democratic freedom was the belief that rational sequence in all things (first causes, first in merit, the original rights of man, original nature, etc.) should break irrational chains of being beholden to genealogies of authority and hierarchy. And the word that was the law of such freedom—as when the American Revolution told itself into being under the principle of freedom of the press—was print.

More stages in this argument might be added (e.g., to address avant-garde, early twentieth-century modernism). But I will draw to a close by jumping to our postmodern/postindustrial present, when the line is being redrawn yet again. So far, I have emphasized the triplet of authority, hierarchy, and sequence (plus or minus continuity), whose reshuffling, I have argued, was the algorithm of modernization. I have not made much of exclusivity or its inverse, inclusiveness (roughly speaking, how small or large the class is that gets to have a vote on modernization).57 Postmodernism, postindustrialism, and globalism today, however, bring exclusivity or inclusiveness to the front of the line (figure 16). Under such aggressively ideological business slogans as teamwork, coopetition, the flat corporation, and disintermediation as well as such equally ideological populist slogans as Web 2.0's collective intelligence, the rule of many, and the wisdom of crowds, inclusiveness now dominates the cluster of values constitutive of linearity—or, as we can now better call it, anti-linearity. We currently believe that everyone, no matter how stupid, wrong, or late to the debate should have their say. Privileging inclusiveness in this way flips the cards all up and down the line such that each of the other nodal values spins around to its opposite: authority to collaboration, hierarchy to many-to-many, and sequence (with or without continuity) to network. As a consequence, rational, first-principle sequence—the signature value of the Enlightenment—loses pride of place and gets pushed to the back of the parade. Damn first principles, first-in-line, first-in-merit (and, by the way, copyright), today's me-too generation says. The many-to-many we wants to get its collective word in edgewise, even if that means blunting the edge. Knowledge today is like a gigantic, world-wide blog with no protection at all against comment-spam: everyone—even the vandal, phisher, or purveyor of stolen software "warez"—is part of a gigantic, stupifying collective intelligence. It is all, not MySpace, but OurSpace.

Yet, of course, the ultimate impression is still historical necessity, as if—to hear the Web 2.0 evangelists tell it—resistance is futile. We are Borg or, rather (citing more Web 2.0 clichés), we are swarm and hive.58 Such is linearity re-reconstructed as the ideology of freedom 2.0. Freedom 2.0 is the postmodern, après-mass-culture ideological critique of an older, modern freedom that had filtered the people through elective representation, controlled media, and other stepping-downs of direct democracy (updated today to networked, open-source, and crowd-sourced democracy). And the word that is the law of the new freedom, of course, is neither the word as such nor print. Essentially, it is a relational database. It is the freedom to break out of whatever sequence of data—ranked by content, value, or date of entry—determined one's station in life to contribute one's random bit of knowledge, atomistic yet cumulative, to the great ur-Wikipedia of contemporary knowledge. It is a hypertextuality whose freest, non-linear form seems to be graphical hypermedia, where all nodes are free to jump to other nodes in abrupt recognitions of new pattern.59

My conclusion: neither in the past nor now is graphical knowledge the opposite of linear, discursive knowledge. Nor can the supposed binary opposition of graphical to linear knowledge simply be told as the history of modernity to postmodernity. Instead, the graphical is a methodological, critical, and ideological reflection upon the linear, and vice versa. Graphical and linear are each other's self-consciousness. What we mean by graphical knowledge today is nothing less or more than the bringing to awareness of the fact that the component values of linearity are reconfiguring once more under the force of a new ideology of freedom—one that, under the pressure of the moment, my impromptu acclaim of "freedom" at the Pauley Symposium in 2006 espoused uncritically as witness to my own submission to the needs of our time.

To be free today, I believe, we need linear thought to be something other than it was in the past, and that need brings to the surface the fact that linearity itself was always a network of concepts that could be freely imagined—we now say "graphed"—otherwise.

My thanks to the Transliteracies Project's History of Reading Group

for illuminating discussions that have informed this essay. My

special thanks also to William G. Thomas III, who patiently insisted

that I write this essay after my talk on a different topic at the

2006 Pauley Symposium (which he organized at the University of

Nebraska, Lincoln) and then, when I finally had a draft ready two

years late, made uncommonly good editorial suggestions.

1 Wallace Stevens, Collected

Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Knopf, 1954), 129-130. "The

Idea of Order at Key West" originally appeared in Stevens, Ideas

of Order (New York: Alcestis, 1935).

2 The conference on "History

in the Digital Age" I refer to was the Carroll R. Pauley Memorial

Endowment Symposium at University of Nebraska, Lincoln, September

21-22, 2006. During the second day of the conference, I gave a

talk entitled "The Future of the Humanities in the Digital Age." In

the ensuing roundtable discussion, Tim Borstelmann of the History

Department at University of Nebraska, Lincoln, asked the question

I quote here. Video recordings of the roundtable discussion and

other conference talks are available on the "Public Lectures" page

of the Digital History web site, ed. William G. Thomas, III, and

Douglas Seefeldt, Department of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln,

retrieved 1 August 2008, lectures.php.

3 The transcriptions

of Tim Borstelmann's question and my response are based on a recording

of the "History in the Digital Age" conference at University of

Nebraska, Lincoln (edited to correct ad hoc, oral infelicities).

4 Talks at the "History

in the Digital Age" conference included Edward L. Ayers,"Civil

War and Emancipation: Visualizing American History"; Peter Bol, "Creating

the China Historical GIS"; and Robert Schwartz, "Railways, Uneven

Geographic Development, and a Crisis of Globalization in France

and Britain, 1830-1914." Video recordings are available on the "Public

Lectures" page of the Digital History web site (cited above). See

also the related articles published on the "Essays" page of Digital

History, retrieved 1 August 2008, essays.php.

5 Franco Moretti, Graphs,

Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History (London;

New York: Verso, 2005), 15, 19, 25. Moretti's identification of

his method as "distant reading" occurs on page 1.

6 Collaborative

online documents refers especially to such recent technologies

as content management systems (CMS), shared online word-processing

platforms (e.g., Google Docs), wikis, and other means of facilitating

multi-author collaboration. Web 2.0 refers to the loose

collection of data architecture, programming methods, interface

styles, many-to-many communication practices, social practices,

and often also self-inflating ideologies (e.g., "collective intelligence," "the

wisdom of the crowd," "the long tail," "open source," etc.) that

arose after the dot.com bust circa 2000 to boost a new generation

of online services and applications (e.g., blogs, wikis, social

networking, mashups). ("The wisdom of the crowd" alludes to James

Surowiecki's, The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter

than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies,

Societies, and Nations [New York: Doubleday, 2004]. For the

early essay that helped define Web 2.0, see Tim O'Reilly, "What

is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation

of Software," 30 September 2005, O'Reilly Media, Inc., retrieved

8 September 2006, http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html.)

On middleware, templates, databases, SQL,

and table-relation diagrams, see below.

7 Such a script was

in fact implemented in many of the student projects I supervised

in a recent set of experimental courses titled "Literature+: Cross-disciplinary

Models of Literary Interpretation"—e.g., the "Close Reading

Re-visited" collaborative project in a graduate-student version

of the course. See the course site, http://english236-w2008.pbwiki.com/FrontPage.

For an explanation of these courses, see Liu, "Literature+," Currents

in Electronic Literacy (Spring 2008), http://currents.cwrl.utexas.edu/Spring08/Liu.

8 Created by a consortium

of Canadian universities, TAPoR is a collection of online text

analysis tools—ranging from the basic to sophisticated—that

allows users to run search, statistical, collocation, extraction,

aggregation, visualization, hypergraph, transformation, and other "tools" on

texts (2003-2006, McMaster University, home page retrieved 18 June

2008, http://portal.tapor.ca/).

For other text-analysis tools, see the guide to online tools that

I keep titled "Toy Chest (Online or Downloadable Tools for Building

Projects)," http://wiki.english.ucsb.edu/index.php/Toy_Chest_%28Online_or_Downloadable_Tools_for_Building_Projects%29.

(The above description of TAPoR was originally written for the

Toy Chest.)

9 Many Eyes is a powerful,

flexible online suite of dataset to diagrammatic visualization

tools. Developed by Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg

of the IBM Collaborative User Experience research group's Visual

Communication Lab, Many Eyes allows users (after registering for

a free IBM alphaworks account) to enter their own datasets in table

format, generate visualizations chosen from a wide variety of styles

(including interactive, dynamic visualizations), share/discuss

datasets and visualizations, and create personalized "topic hubs" to

track data visualizations of interest (IBM Watson Research Center,

retrieved 18 June 2008, http://services.alphaworks.ibm.com/manyeyes/app).

For similar visualization and graphing tools, see Toy Chest (cited

in preceding note). (The above description of Many Eyes was originally

written for the Toy Chest.)

10 For Wordle, created

by Jonathan Feinberg, see Wordle home page, 2008, retrieved 2 August

2008, http://wordle.net/.

For the student project that "performed" Shakespeare's play by

creating a Facebook page for each character, see "Romeo

and Juliet: A Facebook Tragedy" by Helen Skura, Katia Nierle,

and Gregory Gin (members of the undergraduate version of my Literature+

course in 2008), retrieved 2 August 2008, http://english149-w2008.pbwiki.com/Romeo-and-Juliet:-A-Facebook-Tragedy.

On the Friend Wheel social-graph app, developed by Thomas Fletcher,

see Friend Wheel, retrieved 7 November 2008, http://thomas-fletcher.com/friendwheel/;

see also the description on the VisualComplexity site: "Facebook

Friend Wheel," VisualComplexity, ed. Manuel Lima, 31 August 2007,

retrieved 2 August 2008, http://www.visualcomplexity.com/vc/project_details.cfm?id=501&index=501&domain.

11 See C. Wright

Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (New York:

1951; rpt. Oxford University Press, 1956), 63-67. Mills drew on

various government sources for his statistics on the growth of

the white-collar middle class. For my fuller discussion of this

topic, see the second chapter of Liu, Laws of Cool, especially

82 and 431n5.

12 JoAnne Yates, Control

Through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management (Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989).

13 See William Henry

Leffingwell, Scientific Office Management (Chicago: A. W.

Shaw, 1917), and William Henry Leffingwell and Edwin Marshall Robinson, Textbook

of Office Management, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1943).

On Leffingwell's system for writing letters using boilerplate paragraphs

indexed by arbitrary codes, see Liu, "Transcendental Data: Toward

A Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded Discourse," Critical

Inquiry 31 (2004): 69n51.

14 It is intriguing

to compare Stevens' redemptive grid of "emblazoned zones and fiery

poles" with the actual grids of graphic design in the early to

mid twentieth-century.

Stevens worked for an insurance firm. Just

so, the new design profession represented by Bauhaus, the New Typography, and,

later, the International Style (with their credo that form is function) arose

in partnership with modern industry—to the extent, indeed, that European-inspired

design first arrived in the U.S. on the boxes of the Container Corporation of

America (the early sponsor of the new design).

Antithetically, Stevens was artistically

modernist because he also reacted against modernity through a skewed re-imagination

of the actuarial grids of workaday regularity. His "emblazoned zones and fiery

poles" do their work of "arranging, deepening, and enchanting" transcendentally,

extrapolating a kind of ultimate what-if graph or scenario aimed toward "ghostlier

demarcations." Just so, graphic design was modernist because it literally skewed

the box grids of the packaging, poster, advertising flyer, and other media it

had to work with. While it practiced so-called grid design (organizing

a page, for example, into a regular table of columns and rows), it did so against

the grain by emphasizing bold diagonals and other asymmetries. Such skewed designs

were often latently accommodated within an invisible grid, but they manifested

as strikes against the system. (For a fuller discussion of modernist graphic

design with illustrations, see Liu, Laws of Cool, 195-207.)

15 Robert B. Reich, The

Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21st-Century Capitalism (New

York: Random House, 1992). "The Rise of the Symbolic Analyst" is

the title of part 3 of Reich's book.

16 Middleware refers

loosely to a kind of "glue" code that mediates between multiple

software applications or between backend databases and software

applications. A common method for creating Web 2.0-style applications

such as blogs, wikis, and social networking sites, for example,

is to shuttle information between an underlying database and the

Web though an intervening layer of instructions written in a scripting

language (e.g., PHP) that dynamically moves information from databases

to the browser through mediating Web-page "templates" created in

XHTML code with CSS (Cascading Style Sheet) formatting conventions.

The intervening templates—hollow molds for any information

whatever—serve as the staging ground for a variety of middleware

services to assemble data to be output to the user or, working

in the reverse direction, to be input into the database.

TCP/IP (Transfer Control Protocol/Internet

Protocol) is the fundamental data protocol of the Internet that allows information

to be transmitted in error-free, packetized form between computers on the network.

17 E. F. Codd, "A

Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks," Communications

of the ACM 13, no. 6 (June 1970): 377-87. See also Codd, The

Relational Model for Database Management, Version 2 (Reading,

Mass: Addison Wesley, 1990).

18 See Liu, Local

Transcendence: Essays on Postmodern Historicism and the Database (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2008), 249-55. Also see Stephen Ramsay, "Databases," A

Companion to Digital Humanities, ed. Susan Schreibman, Ray

Siemens, and John Unsworth (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004); available

online at http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/ (retrieved

4 August 2008).

19 In SQL, for instance,

the query SELECT * FROM customer_table, transaction_table WHERE

customer_table.id = transaction_table.id ORDER BY last_name, first_name,

street_address, date_of_order, etc. would generate from the

database a particular sequence of data that, depending on the nature

of the information in the database and its table structure, might

yield anything from a purely functional billing receipt to a narrative

argument.

20 See Roland Barthes, "The

Death of the Author," Image -Music - Text, trans. Stephen

Heath (New York: Noonday, 1977); and Michel Foucault, "What

is an Author?" Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected

Essays and Interviews, ed. Donald F. Bouchard, trans. Donald

F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press,

1977).

21 For an against-the-grain

critique of the new collaborative authorship, see Jaron Lanier, "Digital

Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism," Edge,

30 May 2006, Edge Foundation, Inc, retrieved 9 September

2006, http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/lanier06/lanier06_index.php.

Surprisingly, Lanier, who was an early digital pioneer, argues

against Web 2.0 and for the gold standard of traditional, individual

authorship: "When you see the context in which something was written

and you know who the author was beyond just a name, you learn so

much more than when you find the same text placed in the anonymous,

faux-authoritative, anti-contextual brew of the Wikipedia. The

question isn't just one of authentication and accountability, though

those are important, but something more subtle. A voice should

be sensed as a whole."

22 Michael A. Hiltzik, "Sure,

Web's Got Style But Hardly Enough Substance," 13 August 1997, CNN

Interactive, retrieved 12 January 2008, http://www.cnn.com/TECH/9708/13/web.substance.lat/index.php.

23 I discuss the

original cyberlibertarianism extending from the early days of the

personal computer through the era of the pre-2000 Web and dot.com

companies in chapter 8 of Liu, Laws of Cool ("Cyber-Politics

and Bad Attitude"). See also Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, "The

Californian Ideology," extended mix version, undated (shorter versions

dated 1995-1996), Hypermedia Research Centre. School of Communication

and Creative Industries, Westminster University, United Kingdom,

retrieved 13 July 2003, http://www.hrc.wmin.ac.uk/hrc/theory/californianideo/main/t.4.2.html.

24 Scott Karp, "The

Evolution From Linear Thought to Networked Thought," 9 February

2008, Publishing 2.0, retrieved 11 March 2008, http://publishing2.com/2008/02/09/the-evolution-from-linear-thought-to-networked-thought/.

25 Shelley Jackson, "Stitch

Bitch: The Patchwork Girl," 1997, Media in Transition, MIT,

retrieved 1 October 2008, http://web.mit.edu/m-i-t/articles/index_jackson.html.

26 Lev Manovich,

The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 225,

227.

27 See, for example,

the tag-cloud-like "Web 2.0 Meme Map" near the beginning of Tim

O'Reilly, "What is Web 2.0." For a primer on the notion of social

graph, see Alex Iskold, "Social Graph: Concepts and Issues," 12

September 2007, ReadWriteWeb, retrieved 19 June 2008, http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/social_graph_concepts_and_issues.php.

A key, technical critique of the social graph concept (which Iskold

and many others refer to), is Brad Fitzpatrick, (with David Recordon), "Thoughts

on the Social Graph," 17 August 2007, retrieved 19 June 2008, http://bradfitz.com/social-graph-problem/.

28 Shelley Jackson, Patchwork

Girl by Mary/Shelley and herself, CD-ROM (Watertown, MA: Eastgate

Systems, 1995). The Storyspace program, created in the 1980's,

strongly influenced "electronic literature" in the early era of

self-contained hypertext (i.e., standalone hypertext on a single

personal computer prior to the dominance of the Internet). See

the Storyspace home page (2007, Eastgate Systems, Inc., retrieved

19 June 2008, http://www.eastgate.com/storyspace/).

29 Manovich, Language

of New Media, xiv-xxxvi.

30 Shoshana Zuboff, In

the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power (New

York: Basic Books, 1988), 202. See my discussion of the computational

vision trope discovered by Zuboff in Liu, The Laws of Cool,

109-110.

31 One of the relatively

few exceptions to this generalization about business books is Peter

M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the

Learning Organization (New York: Doubleday, 1990). Senge's

influential work focuses in part on shaping an idea of knowledge

appropriate to corporate knowledge work.

32 The Greek graphē and graphein,

of course, are at the root of a whole cluster of such words as grapheme,

paragraph, epigraph, typography, graphic, photograph, diagram,

program, etc. Viewed as a whole, this cluster is bivalently

textual and visual, linear and non-, multi-, or translinear.

Johanna Drucker's writings on the history,

theory, and technology of book design and typography have focused on the way

textual and graphical elements collaborate to make a book, like a program, "work." See,

for example, her recent "The Virtual Codex from Page Space to E-space," A

Companion to Digital Literary Studies, ed. Ray Siemens and Susan Schreibman

(Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007), 216-32, available online. The argument of

a codex, Drucker observes, "is

made in material structure and graphical form as well as through textual or visual

matter. Recovering the dynamic principles that gave rise to those formats reminds

us that graphical elements are not arbitrary or decorative, but serve as functional

cognitive guides" (226).

33 On primary oral

cultures, see Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing

of the Word (London: Methuen, 1982). Ong begins with a review

of Milman Parry's discoveries about the Homeric epics.

34 On the idea of kairos,

see Eric Charles White, Kaironomia: On the Will-to-Invent (Ithaca:

Cornell University Press, 1987).

35 See Ong, Orality

and Literacy, 59-61.

36 See Jack Goody, The

Domestication of the Savage Mind (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1977), esp. 74-111. In oral cultures, list-like phenomena

such as Homer's recitation of ship names or the Old Testament's

genealogies were actually a succession of micro-narratives, each

a stub for narrative improvisation—e.g., "Abraham begat Isaac;

and Isaac begat Jacob; and Jacob begat Judas and his brethren" (see

Ong, Orality and Literacy, 99).

37 Goody, Domestication

of the Savage Mind, 86.

38 Hayden White, The

Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1987) , 6-7.

39 White observes

about this scrap from the Annals of Saint Gall, "Social

events are apparently as incomprehensible as natural events. They

seem to have the same order of importance or unimportance. They

seem merely to have occurred, and their importance seems to be

indistinguishable from the fact that they were recorded" (Content

of the Form, 7). What the annals form lacks, White generalizes,

is a "subject" or principle of cohesion: "the capacity to envision

a set of events as belonging to the same order of meaning requires

some metaphysical principle by which to translate difference into

similarity. In other words, it requires a 'subject' common to all

of the referents of the various sentences that register events

as having occurred" (ibid., 16).

40 In the following

discussion of the transition from scrolls to codex books, I am

informed by work in the history of the book and history of reading

fields that include the following: Roger Chartier, Forms and

Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computer (Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 18-20; Stuart G. Hall, "In

the Beginning Was the Codex: The Early Church and Its Revolutionary

Books," The Church and the Book: Papers Read at the 2000 Summer

Meeting and the 2001 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History

Society, ed. R. N. Swanson (Woodbridge: Published for the Ecclesiastical

History Society by Boydell & Brewer, 2004); James J. O'Donnell, Avatars

of the Word: From Papyrus to Cyberspace (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1998), 50-63; Alberto Manguel, A History of

Reading (New York: Viking, 1996), 126-27; and Peter Stallybrass, "Books

and Scrolls: Navigating the Bible," Books and Readers in Early

Modern England: Material Studies, ed. Jennifer Andersen and

Elizabeth Sauer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

2002).

Many of these works also discuss the relation

of the codex to today's computers, which thus act as the implicit context or

horizon of relevance. On the relation of the codex to computational media, I

am also informed by the works of scholars in the digital humanities fields, including,

for example, Jerome J. McGann, Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World

Wide Web (New York: Palgrave, 2001), and Johanna Drucker, "The Virtual Codex

from Page Space to E-space" (cited previously).

41 See, for example,

Hall, "In the Beginning was the Codex," and Stallybrass, "Books

and Scrolls," 43.

42Peter Stallybrass, "Books

and Scrolls: Navigating the Bible," Books and Readers in Early

Modern England: Material Studies, ed. Jennifer Andersen and

Elizabeth Sauer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

2002).

43 "The Playboy Interview:

Marshall McLuhan," 23 April 2007, Next Nature, retrieved

10 June 2007, http://www.nextnature.net/research/?p=1025.

Originally published in Playboy, March 1969.

44 Quoted in McLuhan, "The

Medium is the Message," Understanding Media: The Extensions

of Man (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1994), 14.

45 For McLuhan's

influence on the history-of-the-book field, witness, for example,

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein. Eisenstein recounts the impact of first

encountering McLuhan's The Gutenberg Galaxy in the preface

to her The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1983), x.

46 On these issues,

see also Roger Chartier, Forms and Meanings, 14.

47 Rolf Engelsing, "Die

Perioden der Lesergeschichte in der Neuzeit: Das statistische Ausmaß und

die soziokulturelle Bedeutung der Lektüre," Archiv

für Geschichte des Buchwesens 10 (1970): 945-1002. For

McLuhan on "mosaic" and "total field" effects, respectively, see "The Playboy Interview" and "The

Medium is the Message,"13.

48Leah Price, "Reading:

The State of the Discipline," Book History 7 (2004), 317.

On Engelsing's argument, see also James Raven, "New Reading Histories,

Print Culture and the Identification of Change: The Case of Eighteenth-Century

England," Social History 23 (1998): 274.

49 Chartier, Forms

and Meanings, 17.

50 Roger Chartier, "Languages,

Books, and Reading from the Printed Word to the Digital Text," trans.

Teresa Lavender Fagan, Critical Inquiry 31 (2004): 143.

51 As I have commented

elsewhere, "one is struck by the mismatch between the intimate

goal of the quest—no less than to get inside the head of

media experience—and the remoteness of the available historical

or statistical observational methods. It is like recent astronomers

telling us about planets around distant stars: no one can see them,

but we infer their presence through complex calculations upon intricate

meshes of indirect data (representing, for example, the slight

wobble of a star) (Liu, "Imagining the New Media Encounter," A

Companion to Digital Literary Studies, ed. Ray Siemens and

Susan Schreibman [Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007], 15; available online).

52 W. J. T. Mitchell, Iconology:

Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1986).

53 For well-known

studies of the classical, medieval, and early modern idea that

the universe is organized ontologically and sociologically from

high to low as a "chain of being," see Arthur O. Lovejoy, The

Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press, 1936), and E. M. W. Tillyard, The

Elizabethan World Picture (1943; rpt. New York: Vintage, n.d.).

54 William Shakespeare, Troilus

and Cressida, The Signet Classic Shakespeare (New York: New

American Library of World Literature, 1963), I.iii.75 ff.

55 In the wake of

industrialization, of course, capital became shorthand for

being first to invent, first in merit, and ultimately first (or,

equivalently, last) to own—a fact that we see nakedly today

in the innovation fetish of contemporary business.

56 Godwin's signature

work on the progress of reason and the improveability of man was Enquiry

Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Modern Morals

and Happiness, ed. Isaac Kramnick (Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin,

1976), originally published in 1793.

57 A fuller discussion

of the Enlightenment with its political revolutions, we note, would

need to address the paradox of valuing both reason and the mob,

both sequence and many-to-many emergence.

58 "Borg" alludes

to the species of networked/hive-mind cyborg creatures so vividly

imagined in the Star Trek TV and film franchise.

59 I have reflected

more fully on the link between the theory of the relational database

and the problem of freedom in chapter 9 ("Escaping History: The

New Historicism, Databases, and Contingency") of my Local Transcendence:

Essays on Postmodern Historicism and the Database (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2008).