Essays

Writing A Digital History Journal Article from Scratch: An Account

In 2001, Edward L. Ayers and I were asked to contribute a "digital article" to the American Historical Review. The AHR had decided to experiment with the form of scholarly communication and production in a series of works that would be peer-reviewed and published as "born digital" pieces of scholarship. Robert Darnton, former president of the American Historical Association, led the effort in 2000 with "An Early Information Society: News and the Media in Eighteenth-Century Paris." Philip J. Ethington produced a sophisticated hypertextual work as well in 2001 on "Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge." Ayers and I followed these with what became "The Differences Slavery Made: A Close Analysis of Two American Communities" published in 2003 in the American Historical Review. What follows here is a look into that process and some reflection on the lessons learned.1

The article appeared in two places. The print edition of the American Historical Review in December 2003 published "An Overview," a short piece Ayers and I wrote to explain the digital article. The AHR featured a link to the digital article both in the print edition and in its online version on The History Cooperative web site. The digital article was published online in its final stage on the server at the University of Virginia. Since then, we have wondered who engaged the article in its various forms and how they "read" it.

Recently, a leading economic historian of the American South wrote me about reviewing his new work on the modernization of the antebellum South. When "The Differences Slavery Made" came up in our email conversation, he explained that he had read "the actual article" but had "not seen the web site." It is clear to us now, in a way that it was not when we set out, that an entirely new form of scholarly communication is emergent in the digital medium and that its structures are not worked out, not nearly as defined as those we are comfortable with.

As a profession we have separated scholarship into understandably important categories, such as peer-reviewed or not, invited or not. In this case the boundaries had been blurred. The piece was double blind peer-reviewed but the readers could certainly guess who the authors were. The piece was invited but with no assurances of publication. "Digital scholarship" was welcomed, in other words, but its process for review would be treated as much as possible like print. The larger issue was embedded in the digital form—would a digital article conform to the conventions of print, or more pointedly, should it do so? Was the "actual" article only what appeared in print—in our case a short overview of the purpose of our digital work? If so, then the "web site" was what we intended as the integration of our analytical argument, evidence, and historiography and what had been thoroughly peer-reviewed by the AHR. Does "a web site" implies imply something less permanent, something less significant?2

Recently I was curious how the "article" was being used. I wanted to find out more about how people were "reading" the digital work and if readers approached the piece differently from the AHR readers. So, I searched on the article's title in Google™ and discovered, to my surprise, a few ways it was being used. The article was assigned in the syllabi of several Civil War and Reconstruction courses, as well as required reading in some history methodology courses. But it was also listed as the example for a journal article with two authors in the 6th edition of the MLA Citation guide.

The article was clearly causing another dilemma for scholars—how to cite it. An Assistant Professor at New York University's School of The Arts posted a note on the EndNote™ help list as he tried to make an entry for "The Differences Slavery Made" in his bibliographic software. His problem was how to decide whether the article was "an electronic source" or a "journal article." "It appears that 'Journal Article' layout doesn't do the trick at all," he wrote the help discussion list in frustration, "and 'Electronic Source' outputs it like this." His question for the list was which format was "closer" to the Chicago Manual of Style standard. So, a "journal article" is not the same thing as an "electronic source" according to EndNote—some one, presumably the authors, might be kind enough to make up their minds.

From the beginning it was clear we were going to bump up against some deeply embedded professional expectations. The large problem we faced, in retrospect, was whether what we were producing what should be classified as an "article" at all. The scholarly article is a highly structured form of communication with a century or more of intellectual craft behind it. Would an "article" in the digital medium, specifically the World Wide Web, bend or break these structures? Would it conform to them? If so, then how conforming would it need to be?

When we started on the project, few of these questions came up. Instead, we were focused on the possibilities we had in mind. We wanted to explore how we might integrate the digital form of presentation with the argument we hoped to make. At the Virginia Center for Digital History we were working closely with a team of graduate students and technical professionals even in this formative stage. Kimberly A. Tryka, the Center's Associate Director, participated in extensive discussions about the structure, style, and form of our work, prodding us to think carefully about everything from footnotes to visual cues for readers. Throughout the process she managed the programming for styling the article and she developed the "reading record" to allow readers to track where they had been in the article. Watson Jennison, Aaron Sheehan-Dean, and other graduate students at the Center plunged into the discussions as well, offering their views on what historians might do in the new medium. This collaborative enthusiasm carried throughout the whole project, but the early discussions we had in the Taylor Room of Alderman Library, VCDH's home, were especially formative. And Kim Tryka, Watson Jennison, and Aaron Sheehan-Dean became the key team that not only helped us implement our ideas but also shaped the project's conceptual approach to the questions of form and narrative structure in important and visible ways.

"Maybe it works along two axes," Ayers wrote me early on, "chronological (political crisis) and structural (facets of social life). The punch line is this: the difference slavery made worked differently along those two axes. It made a certain set of differences structurally, but those were not determinative. It made a different set of differences chronologically, but those were not tied in a one-to-one way to the structural factors. Both were necessary to bring war and it's necessary to understand the relationship between the two to understand the coming of the Civil War."3

With a great deal of enthusiasm, we saw the article as an applied experiment in digital scholarship. Over the last decade, networked information resources had come to play a large role in the work of historians. Most of us have become accustomed to augmenting our library research and professional discussion through digital means. Despite these changes, scholars had only just begun to craft scholarship designed specifically for the electronic environment. We attempted to translate the fundamental components of professional scholarship—evidence, engagement with prior scholarship, and a scholarly argument—into forms that took advantage of the possibilities of electronic media.

Our decisions revolved around three major questions: first, what would the narrative or argument look like, second, how would the navigation and interface work, and third, what technology would support or drive the article. Of course, all of these were interrelated, and decisions about one affected the others. In addition, we planned as one of the fundamental keys to our approach the production of a complex historical geographic information system (GIS) for the communities we were studying.

Right away we recognized how important it would be to break with the narrative structures of the journal article and to use the power of hyperlinking. We looked at all sorts of models and read up on hypertext. In the Journal of Electronic Publishing, for example, we found the following useful analysis by Mindy McAdams and Stephanie Berger. It proceeded along lines we were already imagining for our article:

"We defend two arguments here," they began, "1. The writer does not give up control in hypertext. 2. The reader has always had a large degree of control. If the reader's experience of agency is heightened in hypertext narratives, does it follow that the writer relinquishes authority over the text? That's the control paradox: We contend that the author gives up very little—perhaps nothing at all."

They call the basic units "components" and they identified two key aspects of them: "1. Each component is tightly focused on a single idea, event, description, or problem. 2. No component of an article substantially repeats anything stated in another component in the same article."

McAdams and Berger explained that electronic text and narrative could not be written in the same way as print text and that this difference could not be reverse engineered. In other words we could not write in the standard way for print publication and then cut the text up for digital publication or vice versa. "'Broken apart' is perhaps a poor metaphor," they warned, "it implies a whole that has been damaged. We assert that components ideally are written discretely as components from the very beginning of the process. Extracting components from a pre-existing unilinear text not only proves to be equally (or more) difficult but also appears to produce inferior components."4

With this advice and encouragement we set out to write our "components" explicitly for the digital publication as interlinked but independent pieces of narrative. Forgoing footnotes entirely, we began trying to name the operational premise of our article, calling our technique "forward and backward linking." The article could be called, we thought, "multidimensional,"—multisequential, multithreaded, flexible, modular, component, high articulation, high definition, dynamic.5

We decided to use the digital article to expose the work of the historian, to make our interpretive decisions and the evidence open for others to investigate, test, or arrange in different ways. The basic framework would be modular sets of pages of historiography, evidence, and analysis that would be separate but interconnected. Taking another step, we planned to write the argument and analysis in component parts, again interrelating them through linkages. These at first we called "Findings" then later "Statements" and ultimately "Points of Analysis." Readers, we imagined, would have before them a series of interpretive layers and they would be able to choose their path among evidence, historiography, and our analysis.

In order to facilitate this interlinking, we decided from the start that we would produce the article in the promising, and at the time just developing, new language for the World Wide Web—XML (Extensible Markup Language). We wanted to exploit the dynamic stylesheeting it offered, the ability to take one document—in our case the whole article—and render it to the reader in multiple forms and presentations. We also wanted the ability to interrelate component parts of the text. But an important, long-range concern also led us to XML. We wanted the article to be, as much as possible, planned from the beginning for seamless inclusion in a long-term digital repository and to be integrated into a wide range of future scholarship that might build off of and into it. XML, leading librarians and technology experts assured us, would be the building block of the future.

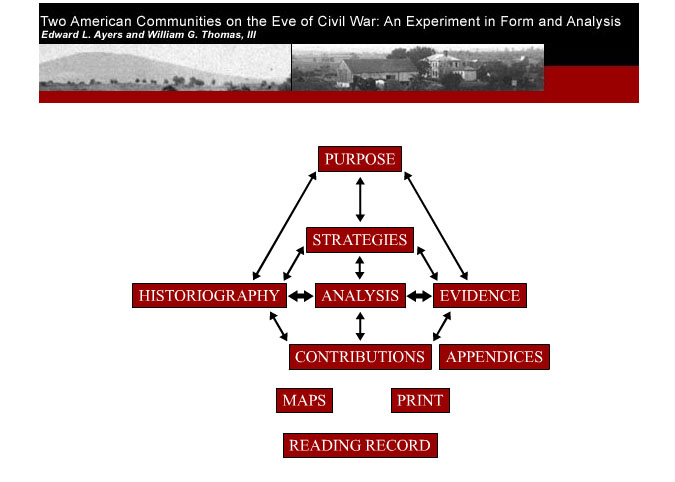

Our first effort at presenting the navigation included a schematic diagram of the multiplicity at the heart of the narrative structure. We intended this dynamic navigator at first as the only way to read the article and in the article's early stages the narrative sequences were equally dynamically generated.

Fig. 1. Our first iteration of the design for the article offered a graphical representation of moving and unfolding choices. In 2002 the Macromedia Flash player was relatively new and reviewers found the design frustrating.

In these early stages we presented the article to a wide range of technologists and historians. At hypertext conferences and XML meetings, the technologist audiences raved about the presentation and the way we were trying to develop a "new rhetoric of scholarly communication." The historians were less sure. Our own history department workshop at the University of Virginia saw the dynamic navigation as distracting, or even worse, as a gimmick. They reacted with some suspicion to the "component" presentation of our argument and hypertext in general. Some saw it as an abdication of authorial "control." A few, it should be noted, thought we did not go nearly far enough with hypertext and hoped we would "break the mould" even more. One of our senior colleagues and a specialist in the Civil War, who read the manuscript with great care, warned us with some jest that the coming of the Civil War, with its long historiography and seemingly long-settled questions, had to be the most ill-suited problem in American history to demonstrate the power of hypertext. At the same time he offered in his criticisms some of the most sustained engagement with both the form and the substance of the digital article we would receive. But another senior colleague, less charitably inclined, attacked our argument as illogical and suggested that the digital medium itself, rather than allowing for a new way to connect evidence through historiography to an argument, was a likely contributor to what he saw as a flawed approach.6

The workshop with the University of Virginia Department of History faculty made us reconsider the hypertextual navigation scheme we had originally designed as the principle interface. We decided to present a choice to the peer review readers for the American Historical Review: they could use the dynamic interface or an alternate text-based interface.

Fig. 2. The authors offered AHR reviewers/readers a choice of navigational interface—static text only or dynamic graphical.

The readers for the American Historical Review included seven scholars of American and Civil War era history, and a few of them had some experience in the development of digital publications. They represented the profession as a whole and, it turned out, they tore apart our first effort. They were, on the whole, right to do so. We had not been very clear about our argument; we had not been clear about the article's navigation; and we had used several technologies that some older systems did not support.

The readers took a dim view of the dynamic navigation and of the corresponding hypertextual narrative behind it. There were too many buttons, too many moving parts, too much obscurity, and too little guidance. Several critics claimed that our argument was obscure or unimpressive. This assessment, it seemed to us upon mature reflection, had two related causes. One was that we simply had not nailed down how to convey the most salient points we wanted to make. The other was that the demands of a non-linear, component-driven structure had worked against reading specifically for "the argument." One reader wrote, "The new format has advantages but also served as a way for the authors to abdicate the historian's responsibility to make sense of incomplete and disparate information." We did not see ourselves, of course, as abdicating anything. But there was a problem: these scholars wanted to "track the argument" and they found "this 'article' . . . difficult, almost impossible, to read as an article because it has no linear structure."

In retrospect, we were probably confronting an irreconcilable problem in our audience and the nature of the medium. On the one hand, we did not want to replicate the traditional article with its linear text and we did not want to add bloated notes and extra material merely because the disk space is nearly infinite. These approaches would not represent an advance over current practice in any way. On the other hand, the modular and extensible structure that we saw as the essential nature of the medium—what Jerome McCann has termed "radiant textuality"—made "tracking" a step-by-step argument nonsensical and perhaps counterproductive. From our vantage point, writing the article in electronic form could not be easily reconciled with these notions of "tracking" and linearity.7

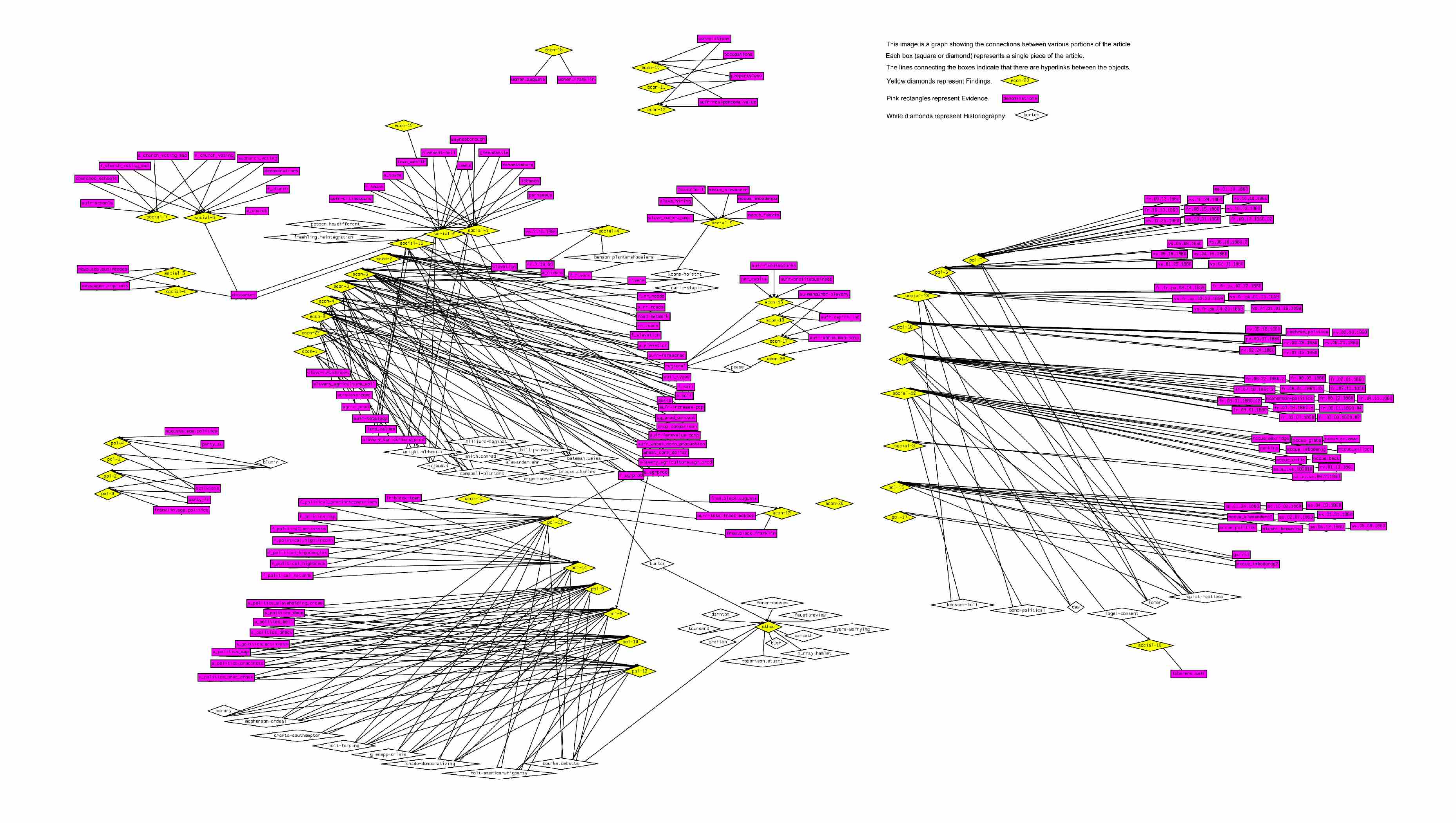

Fig. 3. In this representation of the article's linkages and structure, the components were color-coded and the lines where the authors had made connections. "Findings" were coded yellow, "Evidence" purple, and "Historiography" white. This April 2002 version of the article's structure showed outlying data and used terminology, such as "Findings" the authors later discarded.

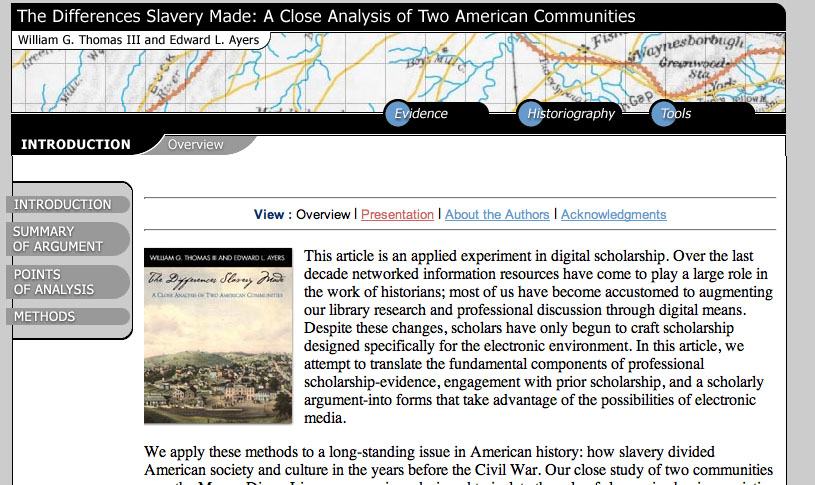

The readers' reports were very perceptive and exceedingly helpful. We did need to sharpen our thesis and we needed the readers' comments to see that. For a second round of reviews by the readers we set aside the "gimmicky" (as one reader called it) Flash™ navigation and rearranged the argument components to make our thesis more accessible. The final result of the article was a streamlined presentation, one with a tight summary section connected to evidence and historiography, and a section we called "Points of Analysis" containing a range of evidence and analysis.

Fig. 4. The final version of the digital article offered an introduction and a summary of the argument but retained the deep interlinking among evidence, historiography, and analysis.

The result according to one set of reviewers was much improved. One reader noted, "Their composite web article argues persuasively that slavery was the defining difference between regions that are in their view, quite similar. Furthermore, XML medium adds a significant twist to this otherwise straightforward analysis. Ayers and Thomas use XML to embrace what historians have always known but have been unable to address in any comprehensible fashion: the fact that slavery is too tightly interwoven throughout Southern society to stand alone as a unit of analysis."8

But this reviewer and others continued to ask two fundamental questions of the article: "Is this a simple, direct presentation? What does this endeavor do better than the standard practice?" Another reader felt even after the revisions that "the rewards [of the electronic article] were simply not commensurate with the effort and confusion involved."

As we assessed the readers' reports and our own internal correspondence we understood the difficulty of joining traditional forms to the electronic medium. My co-author put the matter simply in one of our many discussions about this: "the point of our entire effort is the FUSION of content and form. That's the only reason to do this. We've had an oil & water effect up to this point on argument and form and that leads to confusion and disappointment on both sides. We need to make them one and the same thing."9

As historians experimenting with digital scholarship, we should ask ourselves tough questions. Is it worth the effort? Is it better? Is it useful? These questions seem especially timely now. It seems likely that as more material comes into digital form scholars will seek to create works that not only assemble and annotate digital objects but that engage in more interpretative and analytical presentations of them (whether they had a hand in digitizing them or not). Their works will probably use hyperlinking in ways that open multiple arrangements of digital materials and follow trails of association across digital archives. These pathways fusing interpretation with primary sources could lead to deeply complex renderings of the human experience. Scholars in the future will no longer be as concerned with assembling digital archives and will probably instead turn to the challenging task of manipulating their contents into other forms.

It is too early to tell, of course, what kind of impact these digital works might be having on the field. We do know in the broadest terms that "The Differences Slavery Made" has received a high and increasing level of use. Numerous colleagues have assigned it for upper-level undergraduate and graduate courses on the Civil War, Historical Methods, and 19th-century American History. Students at Brooklyn College, University of Winnipeg, UC Sacramento, SUNY-Albany, and Calgary have read the article. Over 6,500 individual visitors read the article in 2005 and over 11,000 individual visitors did so in 2006. In 2005 these visitors requested over 78,000 pages from the article and in 2006 over 125,000 pages. "The Differences Slavery Made" readers on average requested eighteen pages from the article and they spent over fifteen minutes on a visit to the site (three times the number of click throughs on Valley of the Shadow or Virtual Jamestown).

Looking back at the experience, we learned a few lessons. The first is that the decision about which technology to use as the framework for our article took on much more significance than we ever thought it would. Our choice of XML, while brave and perhaps in the long run useful, has proven problematic. XML's potential for a "semantic web" remains unfulfilled today, and the base language for the web continues to be HTML. Because the article is dynamically generated by readers as they make requests of the XML and the stylesheets that convert it for the web, the article's pages are not available for indexing by Google™ or other search engines.

Another lesson we learned was that readers will need to adapt. So will historians. We have deeply cherished relationships with reading history that for some of us are not really negotiable. Our presumption that readers would want to engage with our article in the way we intended was probably misplaced. We wanted to reveal the process of interpretive history, to show all of our cards, so to speak, and to offer multiple points of entry for readers into our analysis. Yet, we knew very little about how readers use what scholars create in the digital medium, whether the publication is a digital archive or a digital article. We had difficulties understanding anything about how people read or interact with a digital scholarly article in hypertext format. The readers' reports from the AHR were helpful but limited. Until more digital scholarship is created, we will have few conventions or answers about "reading" in the digital medium. Clearly, we will need to evolve the digital environment as we inhabit it.

Since the birth of digital history over the last two decades, historians have experimented with digital archives but rarely with visualization, dynamic mapping, and with what we might call “digital scholarship.” Recently, one intrepid historian published a stirring manifesto in 2003 exhorting his colleagues to start thinking visually with computers, but so far few have risen to the challenge. In fact, one thoughtful reviewer admitted, "to most of us on the outside, history is like an old sofa or a well-worn cardigan."10

We need to cast aside the comfortable if we are to truly understand how to communicate in the digital medium. Already, some humanities scholars have tended to think in conventional terms for digital projects, searching for metaphors, such as "archive" or "exhibit." Others have stressed permanence and stability, favoring works that meet standards and claim longevity. Yet as we wrote our "digital article," we found these goals illusory. Instead, the fluidity of the digital platform for research, analysis, teaching, interaction, and experimentation provided the essential means to our interpretive ends. Digital scholarship may, indeed, require much more commitment on our part than we presently imagine. We historians might have to cast aside our illusions of permanence and our penchant for the "cardigan." If we experiment, however, we might discover that the openness of the digital medium is what allows us both to create vibrant new scholarship and to speak to a rising generation of students.

1 Robert Darnton, "An Early Information Society: News and the Media in Eighteenth Century Paris," American Historical Review 105 (February 2000). Philip J. Ethington, "Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge," American Historical Review (2000). William G. Thomas, III, and Edward L. Ayers, "The Differences Slavery Made: Two Communities in the American Civil War," American Historical Review (December 2003).

2 This concern is reflected in the fact that to date, the work has been reviewed in only one scholarly journal, Kevin Derksen, review of "The Differences Slavery Made: Two Communities in the American Civil War," by William G. Thomas, III, and Edward L. Ayers, Journal of the Early Republic 26.1 (Spring 2006): 157-62. The work is notably absent from the Web Site Reviews section of the Journal of American History.

3 Edward L. Ayers to William G. Thomas, III, January 17, 2001, email.

4 Mindy McAdams and Stephanie Berger, "Hypertext," Journal of Electronic Publishing.

5 Ayers to Thomas, March 4, 2001, email.

6 Allan Megill has recently criticized "The Differences Slavery Made" in a new book on methodology: Allan Megill, with contributions by Steven Shepard and Phillip Honenberger, Historical Knowledge, Historical Error: A Contemporary Guide to Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). See "Introduction: The Need for Historical Epistemology," 1-14. For Megill the article's argument--especially its title--is problematic, because we do not prove that slavery caused the differences we see in the evidence. Megill's logical analysis bears some consideration, but his approach ignores the long historiographical context of slavery in American history in which the article is situated. Megill does not explicitly criticize the digital medium in which the article is presented as his concern is with the logic of argument and evidence in the discipline of history and, indeed, he suggests in fairness that the digital form does not necessarily create the problems he is concerned with. Yet, for us, the digital form became an essential means to make visible slavery's multi-faceted and multi-dimensional effects and to express our argument about the ways slavery arranged the social experience or logic of these communities. Megill's analysis asks us to skip past a generation of slavery historiography and to locate our problem sui generis. Of course, Megill's critique of "Differences" also reveals a deeper divide in the way we approach historical understanding and argument, one that is epistemological.

7 See Jerome McGann, Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web (Palgrave, 2002).

8 Michael Grossberg to Thomas and Ayers, September 18, 2003, anonymous readers reports for "The Differences Slavery Made."

9 Ayers to Thomas, October 15, 2003, email.

10 See David J. Staley, Computers, Visualization, and History: How New Technology Will Transform Our Understanding of the Past (M. E. Sharpe, 2003); Merlin Donald, "Is a Picture Really Worth a 1,000 Words?" in History and Theory, Vol. 43 Issue 3, p. 379 (October 2004).